The tale of the Lost Colony of Roanoke remains one of the most intriguing and enduring mysteries in American history. Established on Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina, this early English settlement vanished without a trace, leaving behind a legacy of questions and theories. This article delves into the historical background, the perplexing events, and the various hypotheses that surround the fate of the Lost Colony.

In the late 16th century, the English made their first attempts at establishing a permanent settlement in the New World.

Under the sponsorship of Sir Walter Raleigh, a group of settlers arrived on Roanoke Island in 1587. Led by Governor John White, the colonists aimed to establish a foothold in the Americas. However, the harsh conditions, strained relations with local Native American tribes, and the challenges of sustaining a new colony set the stage for a historical conundrum.

Governor White returned to England to gather supplies and reinforcements, leaving behind more than 100 settlers, including his own family.

However, the outbreak of war with Spain delayed White’s return for nearly three years. When he finally made it back to Roanoke Island in 1590, he found the settlement eerily deserted.

John White and the others were sure the colonists were there. They had seen smoke from the area they expected the colonists to be the day before, but since it was late in the day, the small fleet of three ships had decided to wait until the next day before landing. The next morning, the ships fired their cannon to signal to the colonists that, after three years, relief had finally arrived. But there was no answer, no sign of life from Roanoke Island.

White went ashore, hoping to find 113 people, among them his daughter Eleanor, her husband, Ananias Dare, and their child, White’s granddaughter, Virginia. The whole world knows what he found instead.

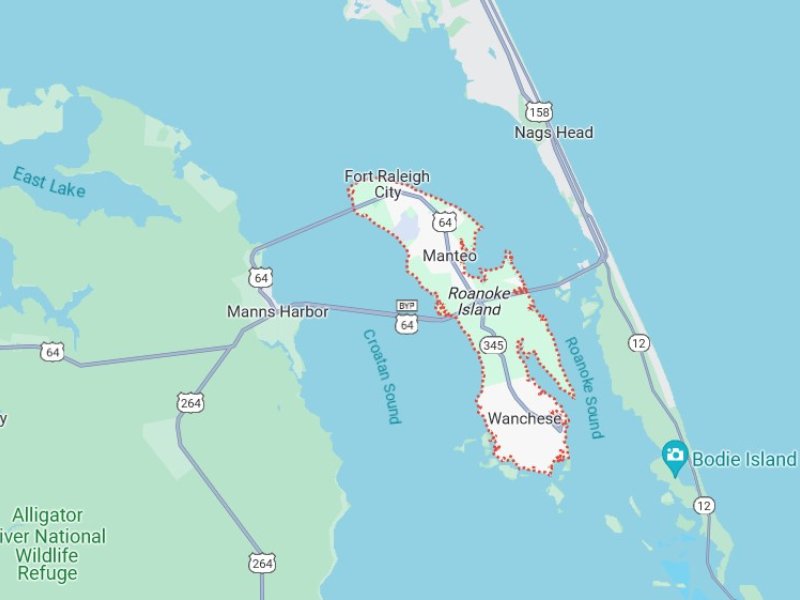

There was no happy reunion, no colonists, just three letters, C-R-O, carved on a tree and a bit further on, carved on another tree, the word “Croatoan.”

The Establishment of Roanoke Colony

When White had left the colony three years before, the colonists had been discussing a move north to what we now call Chesapeake Bay. An agreement had been reached that if the colonists did indeed move, they would carve their destination on a tree with a cross if they had been in distress when they moved. White assumed that the “Croatoan” was a reference to where they had gone, and since there was no cross, White further assumed that the move had not been made in desperation, but that, in itself, was a further puzzle.

Croatoan Island was south of Roanoke Island, and Chesapeake Bay to the north. It made no difference to White. He prepared to go to Croatoan, but fate, which had kept White away for so long, again interfered. A sudden gale blew up and battered the ships. Mooring off the coast was now too dangerous, and the ships were forced to return to England. White was never able to return to mount another search, and subsequent searches found no trace of the missing colonists.

The mystery of the “Lost Colony” had been born.

The colony had actually been the second attempt to find an English colony on the eastern shore of North America. The first, which, like the second, was sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh, had also been a failure.

White had accompanied this expedition, made up entirely of soldiers with a few specialists, and commanded by a cousin of Raleigh’s, Sir Richard Greenville, with Ralph Lane, a twenty-five-year-old favorite of Queen Elizabeth’s, as the colony’s governor. White had been the artist and mapmaker.

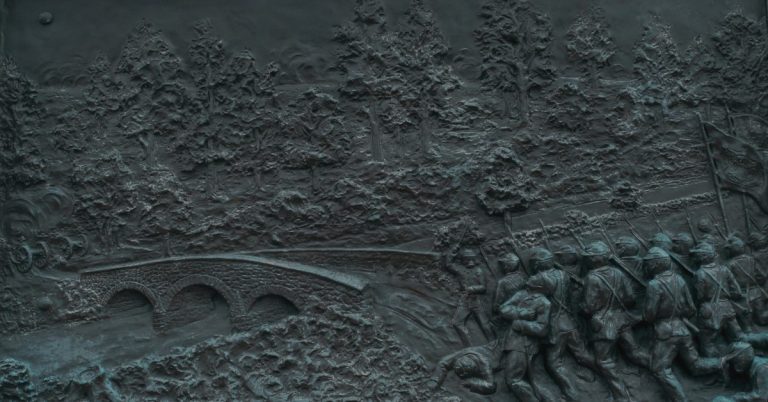

In short order, the colonists managed to alienate the Indian tribes in the area, killing a major chief, Wingina. When Sir Francis Drake stopped at the colony, the colonists abandoned Roanoke and returned to England with Drake.

The second attempt made every effort to succeed where the first had failed. Men, women, and children were in the make-up, showing that these people planned to stay. It was decided that Roanoke Island was inadequate to grow crops for the colonists, so it was planned to settle them north of the Island in the Chesapeake Bay area.

Things began to go wrong almost immediately. The pilot of the fleet, one Simao Fernandes, who had also been the pilot on the first expedition, brought the colonists once again to Roanoke, claiming he had no instructions to take them anywhere else and insisted that the colonists off-load on the Island. An attempt was made, with the help of a friendly Indian named Manteo, who had also been along on the earlier attempt, to establish friendly relations with the local tribes.

Unfortunately, before this could be done, one of the tribes, the Roanoacs, ambushed and killed one of White’s assistants, George Howe, while the latter was fishing.

Making the same mistake the earlier colony had made, White ordered a “revenge” attack on the Roanoacs, but by a tragic mistake, it was the Manteos tribe, the friendly Croatians, who were attacked. The colonists were, with Manteo’s help, able to convince the Croatians that it was just a mistake, but there can be no doubt that any chance for whole-hearted cooperation had been lost.

The ships that had brought the colonists were still offshore, waiting for favorable winds to return to England. Then, the colonists decided that additional supplies were needed, and despite his protest that his place was on Roanoke Island, White was chosen to go. He reluctantly agreed, setting sail on August 27th, 1587, leaving behind his daughter and his grandchild, who had just been born on August 18th. He would never see either of them again.

White hoped to be back the following spring, but fate went out of his way to place obstacles in this path. First, stormy seas delayed his passage back to England, and by the time of his arrival, the threat of the Spanish Armada had caused Queen Elizabeth to commandeer every ship for defense. No ships or any supplies could be spared for White. Even after the defeat of the Armada, the threat of Spain seemed great enough to the Queen to keep England’s ships close to home. It was three years before White was able to return, and he returned too late.

Theories & Speculations about The Lost Colony of Roanoke

In the four hundred years since 1590, numerous theories have been put forth to explain what exactly happened to the people abandoned on Roanoke Island.

1st Theorie

One of these theories is that, despairing of ever receiving aid from England, the colonists attempted to return onboard a small boat that had been left for their use and were lost at sea. Possible, but unlikely. The vessel was a type called a pinnace, carried aboard one of the other ships and then assembled at Roanoke.

Keeping in mind that they had arrived in three ships, it is unlikely that one pinnace would have accommodated them all.

2nd Theorie

Perhaps one of the Indian tribes in the area had risen up and, in a surprise attack, had slaughtered them all.

Again, it seems unlikely. The colonists were aware of the possibility of attack, especially after the killing of Howe, and were heavily armed. An attack, with a resulting massacre, would have almost certainly left traces, yet White saw no such evidence upon his arrival. On the other hand, neither can it be completely dismissed.

If the attack had taken place shortly after White’s departure, there would have been a period of three years for Nature to make the signs of massacre disappear. Was the word “Croatoan” an attempt to name their murders?

The Croatoan and Lumbee tribes of today insist the colony did survive by merging and gradually being assimilated into them.

They point to the fact that gray eyes are often found among them, to their “typically white” features, and to the fact that certain words among them have definite 16th-century English roots. The Lumbees, in particular, point out the fact that the surnames of the colonists are common among them.

Those arguing against this theory point out that all of these things could just as easily be the result of later contact with Europeans, and it is unlikely that only a little more than a hundred people could have that massive of an impact on an entire tribe.

Another theory that has gained weight in recent years combines two of the above theories into the following scenario:

The colonists indeed moved to Croatoan Island, or at least that general area, where a split between two different factions resulted. The majority then moved again, this time to the Chesapeake Bay area, and the smaller group stayed in the Croatoan country, gradually being absorbed by that tribe and the Lumbees.

The larger group prospers, or at least survives, until the early years of the 17th century, when they are massacred, probably by Powhatan, famous in history as the father of Pocahontas. Supposedly, Powhatan confessed this to John Smith of Jamestown after they became friends (following Pocahontas’s alleged saving of Smith’s life). This happened, according to Smith, because Powhatan was afraid that the Roanoke survivors would link up with the Jamestown colonists and the two groups, especially with the Roanokes’ twenty years of experience, would be too strong for him to control.

The problem here is John Smith is not the most reliable witness who ever lived. Much of his adventures in the New World are today dismissed by scholars as no more than Smith’s fantasies.

Archaeological Clues and Recent Discoveries

In recent years, archaeological excavations and modern technology have provided new insights into the fate of the Lost Colony. Artifacts found on Hatteras Island suggest that some of the settlers may have indeed integrated with the Croatoan tribe.

Furthermore, the discovery of a hidden fort symbol on John White’s map has led researchers to explore other potential settlement sites.

The mystery of Roanoke continues to capture the imagination of historians, archaeologists, and the public. The story of the Lost Colony is more than a historical enigma; it’s a narrative that speaks to the challenges, risks, and uncertainties of early colonial ventures. It reminds us of the complexity of human history and the many stories that remain untold or half-told.

While the true fate of the colonists may never be fully uncovered, the story of Roanoke continues to intrigue and inspire, serving as a fascinating chapter in the broader narrative of American history. As we piece together clues and ponder theories, the legacy of the Lost Colony of Roanoke reminds us of our relentless pursuit of knowledge and our desire to understand the past.

Someday, perhaps precise evidence will be found telling what exactly happened, but until then, the “Lost Colony” will remain one of history’s greatest mysteries.