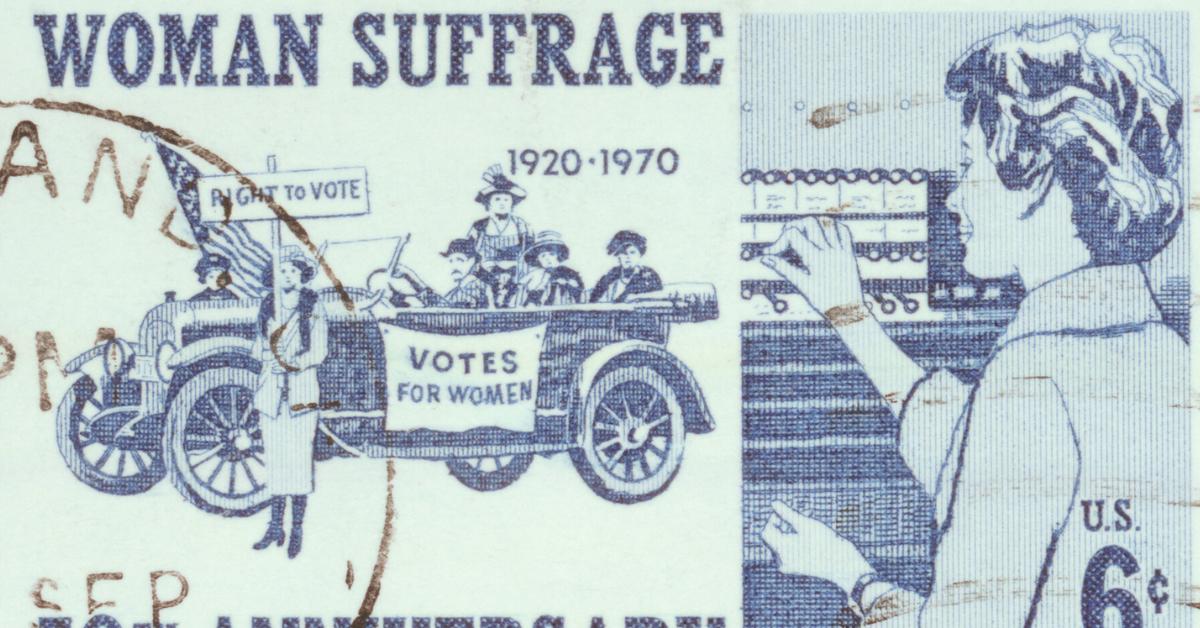

The women’s suffrage movement in the United States achieved its goal of winning full voting rights for women when the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920.

The journey to women’s suffrage in the United States is a vivid chronicle of perseverance, bravery, and unwavering determination. It’s a story that unfolds over decades, featuring women who dared to imagine a society where their voices, hitherto muted by the stringent dictates of patriarchy, would finally resonate in the halls of democracy. This narrative is not just about the attainment of voting rights; it’s a broader testament to the relentless human spirit fighting for equity and justice.

The Dawn of a Movement

The suffragist movement in the United States was an outgrowth of the general women’s rights movement that officially began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. Several leading figures in the antislavery movement had also begun to question the political and economic subjugation of women in a society that claimed to be a democracy. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Martha C, Wright, and Mary Ann McClintock issued a call for a convention concerning the rights of women. That convention met in Seneca Falls, New York, on 19-20 July 1848.

The convention adopted a “Declaration of Principles,” deliberately modeled on the Declaration of Independence, which stated, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal. . . .”

In addition to the Declaration of Principles, the Seneca Convention also asserted that women should have the right to preach, to be educated, to teach, and to earn a living. The delegates passed a resolution stating that “it is the sacred duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.” With these words, the struggle began in earnest to win full voting rights for women in the United States.

The most influential leaders of the women’s rights movement in the second half of the nineteenth century were Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. However, the united struggle for women’s voting rights broke into two factions following the Civil War.

Led by Anthony and Stanton, those who believed that they should seek an amendment to the U.S. Constitution formed the National Woman Suffrage Association in May of 1869. Later that same year, the American Woman Suffrage Association was formed by those who believed the most effective strategy would be to pressure state legislatures to amend state constitutions. The leaders of this group were Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe.

The two organizations merged in 1890 as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), with the intention of simultaneously pursuing both strategies.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton became the first president of the new organization (1890-1892), followed by Susan B. Anthony (1892-1900), Carrie Chapman Catt (1900-1904), Anna Howard Shaw (1904-1915), and then Catt again (1915-1920). In 1920, when NAWSA was dissolved after achieving its goal of women’s suffrage, it was replaced by the National League of Women Voters” established in Chicago in 1920 to educate women about how to use the newly won vote. In time, the National League of Women Voters became the League of Women Voters, which currently operates under that same name. When the National League of Women Voters was first established, Carrie Chapman Catt was elected as its honorary president.

The efforts of the women’s suffrage organizations met with determined resistance. By seeking a voice in politics, women were challenging the conventional belief that women’s proper sphere of influence was domestic while men properly dominated the public sphere, including the political process. Even many women deplored the effort to extend the vote to women.

In 1911, Josephine Dodge, the wife of a leading New York capitalist, formed the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Like many other anti-suffragists, Dodge advised women to influence policy from behind the scenes through their influence on men. By involving themselves in politics, she insisted, women would undermine their moral and spiritual role, as well as create chaos by meddling in matters that were beyond their understanding.

The Amendment of Hope

The first partial suffrage was achieved when some states allowed widows to vote in school board elections, which many people considered to be a reasonable extension of a woman’s concern for issues having to do with home and family.

The first extension of full voting rights to women came in 1869 in the Wyoming Territory.

When Wyoming entered the Union as a state in 1890, it was also the first state to provide for women’s suffrage in its Constitution. In 1893, Colorado extended the franchise to women, followed by Utah and Idaho in 1896. Fourteen years later, in 1910, the state of Washington also enfranchised women.

One by one over the next eight years, states began to grant voting rights to women: California (1911); Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon (1912); the Alaska Territory (1913); Montana and Nevada (1914); New York (1917); Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota (1918).

In Illinois, women won the right to participate at the federal level by voting in presidential elections (1913). Nebraska, North Dakota, and Rhode Island followed (1917), then Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee, and Wisconsin (1919).

This piecemeal pattern of suffrage achieved to varying degrees, state by state, was a slow and uncertain process. The leaders of the suffragist movement understood that even as they pursued such state-by-state tactics, they must also push for full suffrage at the national level, which could only be achieved through an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Just such an amendment, called the “Anthony Amendment,” was introduced in the Senate in 1878 but was defeated by a vote of 34 to 16.

The Amendment read, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

The same Amendment was reintroduced in each succeeding Congress, but it made no progress until 1914 when NAWSA presented Congress with a petition signed by more than half a million people. The Amendment was defeated in the Senate by a close vote of 35 to 34 in 1914 and in the House the next year by a vote of 204 to 174. Though both votes fell short of the necessary two-thirds majority, they were much closer than past votes had been.

In an attempt to rally national support for the Anthony Amendment, Alice Paul organized a huge parade down Pennsylvania Avenue on the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s first inauguration. But the peaceful parade degenerated into a riot when thousands of hostile male spectators broke into the ranks of the marchers and tried to block their passage. Essentially, the women had to fight their way down Pennsylvania Avenue with the help of men who supported the women’s suffrage movement. Troops had to be called in to restore order, and hundreds of people were hospitalized.

Later, in 1913, Alice Paul organized the Congressional Union, later called the Woman’s Party, to lobby Congress on behalf of a constitutional amendment granting the vote to women. Paul modeled her organization after the more militant suffragists in Great Britain. The Woman’s Party directly confronted those in power with the discrepancy between America’s supposed ideals and the reality that more than half of its adult citizens were not enfranchised. In 1917, the Women’s Party embarrassed President Wilson by picketing up the White House around the clock. When many of the demonstrators were arrested and jailed, they went on a hunger strike and were force-fed.

In both cases, “the 1913 parade and the brutal force-feeding of jailed women in 1917,” the abuse suffered by respectable middle-class women outraged public sympathy and elicited sympathy for the suffragist cause. Such sympathy was reinforced by a shift in the tactics used by some of the movement’s leaders. They began to argue for women’s suffrage within the framework of traditional views about women’s proper role in society. Rather than focusing on issues of justice or equal rights, they argued instead that women would bring their moral superiority and maternal instincts into the often brutal arena of politics. Thus, the image of the suffrage movement began to be softened for public consumption. Suffragists were no longer seen merely as radicals who wished to disrupt the natural social order but rather as agents for extending female benevolence outward from the family to society as a whole.

This image was also helped by the fact that in the 1890s, the suffragists allied with the Women’s Christian Union (WCTU). Although the WCTU’s main objective was to enact restrictive liquor laws, the group also agitated for social reform on many other fronts. The WCTU came to support the cause of women’s suffrage on the grounds that without the vote, women lacked the power to protect their homes and families and defend morality.

The active participation of women in the nation’s war effort from 1917 to 1918 also helped to win support for a constitutional amendment enfranchising women. By a vote of 274 to 136, the Amendment was passed by the House on January 10, 1918. On June 4, 1918, it was passed in the Senate by a vote of 66 to 30. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the Amendment, and it officially became part of the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920, as the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Which was the first state to grant women the right to vote?

Wyoming was the first territory (and later, state) in the United States to grant women the right to vote. This historic event occurred in 1869, over 50 years before the 19th Amendment was ratified. Wyoming’s bold move was partly motivated by a desire to attract more women to the sparsely populated territory.

Who was the first woman to vote in the U.S.?

Seraph Young made history as the first woman to vote in the United States under a women’s equal suffrage law during a municipal election in Salt Lake City, Utah, on February 14, 1869. This milestone event predated Wyoming’s first election, where women voted, highlighting an important moment in the journey toward universal suffrage in the U.S.

Impact of Women’s Suffrage on U.S. Politics

The impact of the Women’s Suffrage Movement extends far beyond the acquisition of voting rights. It fundamentally transformed the social, political, and cultural fabric of the United States. The movement catalyzed changes in other areas of women’s rights, laying the groundwork for future legal and societal reforms. It also inspired movements around the world as women in other nations sought to emulate the successes of their American counterparts.

Although women had finally won full voting rights, they did not really begin to have access to most political offices until well into the 1970s, and even today, at the start of a new millennium, women are found in political office at a rate far lower than one would expect from a group that represents one-half of the nation’s population.

Furthermore, women’s access to the highest and most powerful political offices is still severely limited, both by prejudice and by the shortage of female office-holders at all levels, for it is from the ranks of such lower-level office-holders that the candidates for the highest offices are recruited. While many other nations have accepted the leadership of women, the United States is still unlikely to accept the idea of a woman as president – at least for now.