As society turns to television as its primary source of news, it is obvious that its members will not hear the full story. Television is a unique medium that has obvious limitations. The need for dramatization, the problem of time constraints, the need for visual content, and the need to clarify complex stories all factor into the problem. Even with 24-hour news shows, the real story is often not investigated in-depth like it is in other media sources such as newspapers, magazines, or even the Internet. Our state of democracy has declined as a result of television.

The rational choice theory says that ordinary citizens should be able to make political choices based on a broad range of political information, but television does not supply enough facts for the public to make educated decisions when it comes to voting. Most citizens say that television news provides them with enough information, and many purposefully turn to television for this information. Television encourages viewers to make political decisions based on emotions rather than engaging in logical thinking to make such choices. Most people focus their learning on a limited number of political areas that are important to them, but television news provides tidbits of information about everything rather than focusing on the two or three most important stories of the day.

Although news magazine shows, such as 60 Minutes, feature three or four stories, each about twenty minutes in length, the shows often appeal to emotion, and the medium has a hard time in helping people engage in their own thinking. The print medium is less reliant on emotions, so it is taken more seriously. “It remains a widely acknowledged fact that the substance of many political television newscasts is poor.”

Graber’s research proves that even though citizens know a little bit about important political issues, there are important aspects of politics that they do not know. Large numbers lack knowledge on important policy issues that could directly affect their lives such as how to apply for public assistance programs that are designed for them. A democratic society should offer political information to citizens in a way that they can clearly understand.

Since television news is reliant on pictures, the nature of it being an audiovisual message means that it does a better job at showing particular conditions such as a parade while words do a better job at explaining how often and under what circumstances a condition occurs.

The later types of stories are not conveyed on television because some stories cannot be combined with such a graphic, and audience members do not like seeing talking heads. Even though visuals are important in some stories, it’s obvious that people can make connections to other related images, “people learn which larger scenarios certain visuals suggest regardless of whether these scenarios are even related to these visuals during a particular news presentation.”

The film Network highlighted the awesome power television has on its audiences. The film made in 1970’s made many predictions on the future of television and how television news would continue to be formatted as “entertainment”. Howard Beale accurately predicted how powerful television would become. “At the bottom of all of our terrified souls, we know that democracy is a dying giant, a sick, sick, dying decaying political concept rioting in its final pain. I don’t mean that the United States is finished as a world power. The United States is the richest, most popular, most advanced country in the world.

The communists are deader than we are. What is finished is the idea that this great country is dedicated to the freedom and flourishing of every individual in it. It’s the individual that’s finished. It’s the single, solitary human being that’s finished. It’s every single one of you out there that’s finished. Because this is no longer a nation of independent individuals,” said Howard Beale.

Alterman implies that it is easier for print journalists to do investigative journalism because they do not have to answer to as many people. Print journalists only answer to editors, publishers, and corporate executives who are at the top of the hierarchy. Television journalists, on the other hand, must answer to producers, executive producers, and network executives who are concerned about ratings, advertising profits, advertisers, audience, and corporate owners. Alterman argues that all forms of media do a disservice to consumers by not challenging the status quo.

As the neoliberal environmental critic Greg Easterbrook told Howard Kurtz, ‘The media have done a shockingly poor job of not challenging either the left or the right on [the environment].’

Newspapers have proven to be a better medium than television. Newspapers allow writers to write letters to the editor about issues affecting their communities. Despite the amount of money the big three networks get, they fail to put enough affiliate stations across the country to cover each community accurately. For local news, people are forced to turn to print journalism. For example, in Connecticut, unless someone was killed in Willimantic, the city rarely gets news coverage. NBC 30 prides itself on covering “Connecticut News” when, in actuality, it mainly covers the major metropolitan areas of Connecticut, such as Hartford and New Haven.

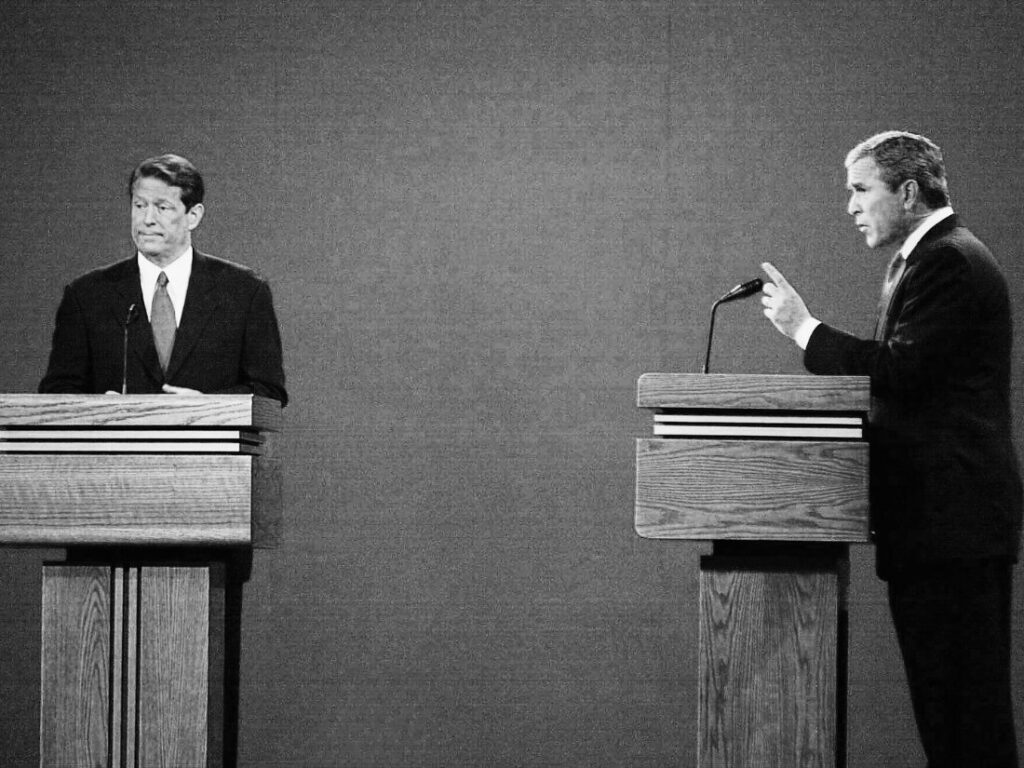

Graber explains that television forces watchers to judge candidates based on their physical appearance and their body language. Visual and non-visual cues are ingrained in memory and voters remember these when they make their decision on who to vote for. Of course, a politician’s facial expressions and body language do tell some about one’s feelings and reactions to situations, it should not replace judging candidates on the issues.

Postman explains that television has lowered people’s attention spans exponentially. He gives the example of the famous debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas would speak for one hour, Lincoln would reply in one hour and a half, and then Douglas gave a half-hour reply to Lincoln’s rebuttal. The debates that went on were not even presidential debates but merely debates discussing political issues. Most audience members would not have the patience to sit through a three-hour debate.

These were people who regarded such events as essential to their political education, who took them to be an integral part of their social lives, and who were quite accustomed to extended oratorical performances.

Today, many engage in debate coverage rather than watch the debate themselves. Studies that were conducted already have proven that the more a person watches the actual debate, the less likely that person will be influenced by the portrayal of the candidate in campaign coverage.

Graber further argues that the audience is unable to reflect on television messages because of the fast pace of words and pictures. Hidden cues in pictures are often missed and alternative meanings are missed as well. Graber cites research done by Shanto Iyengar and Donald Kinder in 1987 which concluded that when journalists frame news stories around emotional experiences of individuals or groups, audiences mistakenly get the impression that the story only affects this individual and not society at large.

Graber also says that deception is often used in audiovisual communication, both unintended and deliberate. Content, structure, and unrelated images all contribute to the ability of audiovisuals to create a false sense that the concepts discussed are linked together. Graber notes that Roderick Hart, in his book Seducing America (1994), says that another danger of the audiovisual medium is that average Americans bring images of the world into their living rooms believing that they are powerful when, in fact, they are powerless. Graber also cites Postman, who, in 1984, explained that viewers feel overconfident about their ability to judge political events as a result of television.

The focus on human tragedy on television makes stories into mini-dramas. The ability for television to create mini-dramas can also be observed in its coverage of political campaigns. Campaign hoopla stories tend to distort the size of crows and misrepresent their mood by selectively focusing on the most enthusiastic or the most hostile groups without adequate explanatory comments.

Repetition deepens the memory traces so when pictures are repeated over and over again, most audience members will remember those pictures rather than the actual facts going on at the time. Americans saw two planes hit the World Trade Center Towers in New York City dozens of times on television and remember that picture, but when asked what times the towers were hit, fewer will remember that since it is a fact and not a visual. If the scenes of the pictures are distorted because of a lack of appropriate information, events can be permanently misconstructed in citizens’ minds.

In Jamieson and Waldman, the idea of performance and the audiences of politics is defined. The larger audience, the voting public, is one audience, while the other is the press, which is both an audience member and a participant. They edit politicians’ roles and tell the public how their performance should be judged. Television allows the ability for a politician to have sound bites, five or ten second spots of the actual speech.

We recall these exchanges not because they were so compelling that they implanted themselves forever in our memory but because, in the wake of each debate, they were played on television and quoted in newspapers again and again.

In today’s politics, those who are unable to come up with a sound bite that the media chooses to associate with the candidate or even choose to use at all have a low chance of winning votes from the American public. Television brings political speakers into an intimate distance from citizens, and political speech becomes more personal. The technology of radio simply allowed citizens to stay at home to hear political speeches rather than go to the town green. The ability of a candidate to connect to individuals on a personal level is a premium, and examples of such candidates are Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton.

One of the dangers our democracy will be facing is the continual decline in the number of viewers who actually watch presidential debates on television. Even though television, as a medium, has its faults, citizens watching television for news have a clear advantage over those who watch television for purely entertainment purposes. About 60% of American televisions tuned in to each of the John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon debates in 1960. The final debate between George W. Bush and Al Gore – for the 2000 election, an election as close as the one in 1960, was watched by less than 26% of American homes. It’s interesting to note that the two 1960 debates had 100 million fewer Americans than the debates in 2000, and many homes in 1960 did not have television.

Numerous studies have been conducted to study whether television’s political coverage closes the knowledge gap that currently exists. The knowledge gap claims that those from high socioeconomic backgrounds are more politically knowledgeable.

Those from low socioeconomic backgrounds are less politically knowledgeable. Socioeconomic background is defined as a combination of wealth and education and is usually defined by families, not individuals. This is not to say that individuals cannot emerge from another socioeconomic background, however. The media’s next challenge is to narrow this gap. They have attempted to narrow this gap, but it failed, and educated people became more educated from television news while those not politically educated did not obtain any political knowledge from television sources.

Background music can arouse people’s feelings and thoughts just as much as visual symbols, and sometimes, people may be unaware of this arousal. Background music is often used in campaign commercials but also during party national conventions. The music oftentimes becomes the main message. Even the overall style of a message can influence how a viewer perceives it. Examples of this include the type of structure, colors, use of still photographs, camera positions, and the types of subjects that are in the message itself.

In an analysis done on politically informative segments on nightly national newscasts from 1997-1998, foreign issues were covered the most, with a total of 43 minutes. General domestic issues were covered second, lasting a total of 31 minutes and 30 seconds. Social issues were covered third, with a total of 29 minutes and 40 seconds. Environmental issues were covered fourth, with a total of 24 minutes. Economic issues were covered the least, with a total of 15 minutes and 50 seconds. The analysis was conducted on November 23, 1997, December 29, 1997, January 13, 1998, February 11, 1998, March 5, 1998, April 17, 1998, and May 9, 1998. Coverage of CBS was a 30-minute segment conducted on Sunday and Wednesday, coverage of NBC was a 30-minute segment conducted on Monday and Friday, coverage of ABC was a 30-minute segment conducted on Tuesday and Saturday, and coverage of CNN was a 60-minute segment conducted on Thursday.

Graber says that this data proves that “television does devote substantial slices of time to informative stories about important happenings in the viewers’ world”.

On average, it seems that CNN spent more time covering general domestic issues and foreign issues than the other networks. Even though it appears that many serious issues get covered by the media, Graber says that about 80 percent of stories are covered in less than three minutes in a news broadcast with just 33 percent of those being covered in less than one minute. This \means that there is little time to explain complex issues.

The Network clearly depicts the negative consequences of television and how excessive viewing of television could distort both the audience’s and the journalist’s sense of reality. As Max tries to talk sense into Diana, he tells her how she has lost reality. “You’re television incarnate, Diana. Indifferent to suffering. Insensitive to joy. All of life is reduced to the common rubble of banality. War, murder, and death are all the same to you as bottles of beer. And the daily business of life is a corrupt comedy. You even shatter the sensations of time and space into split seconds and instant replays”.

Arthur Jensen, the head of UBS, puts it best when he says, “There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT, and AT&T; and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today.” Democracy, as our forefathers envisioned, is slowly eroding as citizens care less and less about politics, read fewer newspapers, and generally fail to become interested in issues that directly impact them. In a democracy, people must take a stand against actions they do not agree with. Students at Connecticut State Universities failed to conduct massive rallies at the State Capitol in protest of the tuition hike, and many are opposed to the hike but are not as concerned as they should be.

Television has lowered our attention span and caused us to be more compliant, and unless news coverage increases in quality and quantity, it will continue to be a major threat to democracy. Our public’s limited understanding of the political issues and the political process will further widen the gap between politicians and the people, and if the politicians fail to hear what the people want, they can not be expected to solve problems that they either do not know exist or do not hear complaints about.