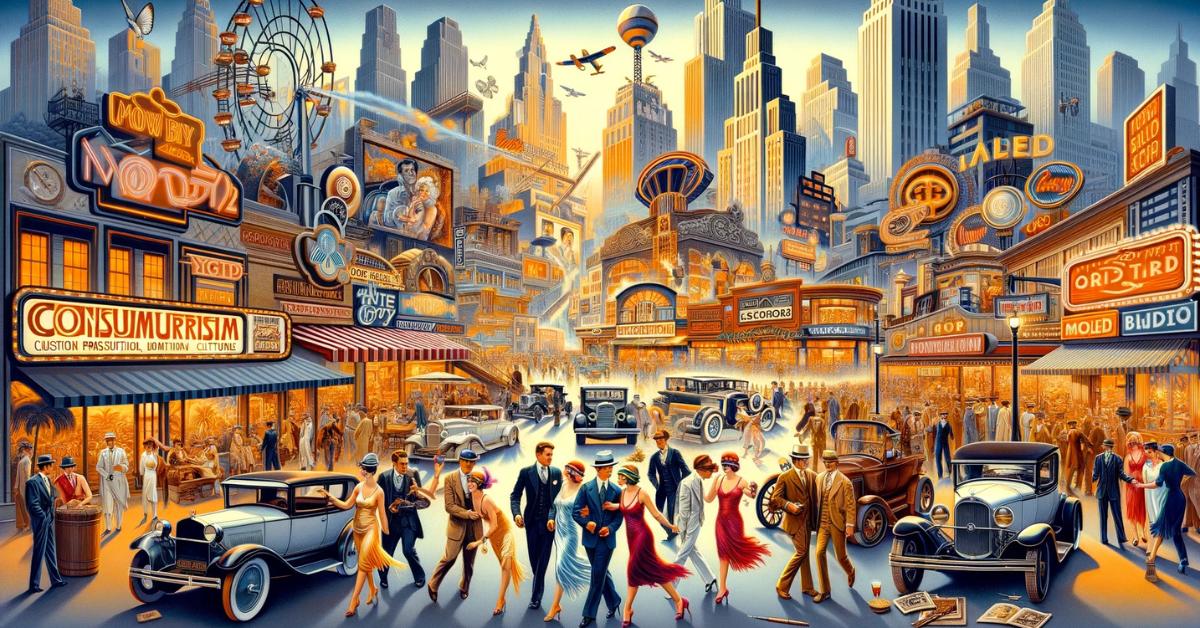

Post-World War I, American society became increasingly standardized as automobiles, electric appliances, and mass entertainment became available to ordinary Americans.

At the end of World War I, the American industry, whose capacity had significantly expanded during the conflagration, needed new markets to sustain the production of goods. These markets were soon made available by the emerging advertising industry, which specialized in creating and maintaining the need for a variety of modern products and services.

Advertising campaigns, the radio, and the movie industry standardized American life and undermined regional diversity, but at the same time, helped forge a national culture and reinvent behaviors.

Although the consumerist attitude encouraged waste and triggered an economic downslope movement toward the Great Depression, it also offered ordinary Americans opportunities they had never dreamed of in the previous decades.

An Era of Emancipation and Mass Entertainment

As life in the U.S. became increasingly standardized, workplace routines caused Americans to shift their attention toward leisure-time activities. The monotonous assembly lines and the harsh managerial supervision no longer allowed workers to take pride in the individuality of their work.

Prospects of advancement were almost nonexistent, and the skills required to perform a job became narrower. Workers were now mere links in a chain of industrial production. In this context, pastimes became vital sources of fulfillment.

In their spare time, people went to the movies, listened to the radio, and gathered in stadiums to watch professional baseball and college football. In 1926 and 1927, the first radio networks, NBC and CBS, were established. All across the country, people listened to the same shows and became obsessed with the same tunes.

Radio sales soared, approaching seven million sets by 1927, according to Boyer and Clark’s The Enduring Vision – A History of the American People, Vol. II.

While the radio was an indoor experience that people enjoyed in their homes, movie theaters allowed them to leave behind the comfort of their daily surroundings and participate in the adventures that the big screen promised. The motion picture industry underwent a spectacular development after 1927 when the feature-length film The Jazz Singer introduced synchronized sound. Movie stars, radio celebrities, and professional athletes became heroes, symbols of the escape from a regimented existence.

Although inventions such as the radio and the movies further standardized culture, they opened the doors to a previously unknown world. While the airwaves and the big screen mentally transported Americans to places they had never had access to before, another increasingly popular invention, the automobile, allowed them to take long drives in the country, plan family vacations, and visit faraway cities.

For decades, the automobile had been a luxury reserved for rich Americans. In 1907, Henry Ford announced his intention to create a car that would be available to the average working family. By 1920, his plant at Highland Park produced a finished Model T every sixty seconds, according to “Industries: Business History of Automotive Manufacturers/Suppliers (A-G).”

As Ford soon discovered, the key to making an affordable automobile was an efficient, standardized production process. By the late 1920s, thousands of identical cars roamed the country’s roads.

The rise of the consumerist culture had perhaps the most dramatic impact on the role American women played in society. As work and behavior patterns shifted, domestic life was forever altered.

The hours of housework were reduced by the new appliances now available to many families. Bakery bread, canned food, and refrigeration allowed women to spend less time on food preparation. Many women went to work outside their homes as sales clerks in the newly-created department stores and as office employees in advertising firms. While they joined the workforce in increasing numbers, they also became the main consumers.

Magazines and advertising campaigns targeting the female population lured women toward supermarkets, department stores, and mail-order catalogs. The mass-produced automobiles allowed them more freedom of movement at a time when old conventions and morals were replaced by a more relaxed behavior. In the Roaring Twenties, the American woman became a less domestic, less inhibited, and more active participant in modern life.

The rise of Advertising in the 1920s

Imagine a time when cigarettes were touted as health aids, cigarettes! Or women were told their greatest power lay in shining floors. Welcome to the Roaring Twenties, a decade where jazz ruled the airwaves, fashion defied convention and advertising, and it learned to roar.

Prior to the 1920s, marketing was a hush-hush affair. Products whispered their charms in print ads tucked away in newspapers and magazines. But as flappers bobbed and the Model T sputtered onto the scene, consumerism exploded. And with it, advertising shed its timid skin and donned a sequined flapper dress, ready to dance on rooftops and shout its message from the highest billboard.

Here’s what fueled the advertising revolution:

The Rise of Mass Media

Radio crackled to life, bringing voices and jingles into living rooms across the nation. Hollywood churned out silent epics, weaving product placements into celluloid dreams. Magazines overflowed with glossy ad spreads, each page a kaleidoscope of vibrant promises.

Suddenly, advertising wasn’t just something you read; it was an experience, a serenade, a silver-screen spectacle.

The American Dream on Steroids

Post-WWI, America pulsed with optimism. The Great Depression was a looming shadow, but for now, prosperity gleamed like a Gatsby mansion party.

Advertising tapped into this collective yearning, portraying a world where happiness could be bought in installments, where every shiny new gadget was a passport to paradise.

Own a car? You’re not just driving; you’re conquering open roads!

Smoke a Lucky Strike? You’re not just inhaling tobacco; you’re exhaling sophistication!

The Science of Seduction

Gone were the days of dry facts and feature lists. Psychologists were recruited, crafting ads that spoke not just to logic but to emotions and desires. Fear of missing out? Check. Appeal to vanity? Double check. Sex sells?

Well, that one practically wrote itself (though with a whole lot more euphemism back then). Advertising became a master manipulator, whispering sweet nothings in the ear of your deepest insecurities.

The 1920s advertising boom transformed the landscape permanently. Jingle bells became battle cries, billboards became cathedrals of commerce, and brands became household gods. We may scoff at some of the era’s outlandish claims, but there’s no denying the lasting impact. Today’s targeted ads, catchy slogans, and influencer marketing – all trace their roots back to that vibrant, audacious era when advertising learned to strut its stuff and sing its siren song to a nation hungry for the next big thing.

So, the next time you see a perfectly-lit Instagram ad for a miracle smoothie or hear a celebrity extol the virtues of a new phone, remember the Roaring Twenties. That’s when advertising truly found its voice, and the world has been listening ever since.

The Down Side of Mass Production and Mass Consumption

While most Americans enjoyed the new prosperity, few people were aware of the problems that threatened long-term economic stability and the environment. Energy consumption soared in the 1920s due to the electric appliances replacing manual labor in many homes.

Plants and car exhaust emissions exerted an increasingly heavy toll on the environment. However, pollution and the diminishing wildlife seemed distant threats to most Americans.

In addition to the environmental setback, the automobile also had a significant social and cultural impact on American life. The accident rate continued to increase throughout the decade, and urban planners now had to deal with new challenges such as traffic jams, parking concerns, and an insufficiently developed infrastructure.

Moreover, the mobility that cars allowed affected family cohesion. Young people who had access to automobiles spent more time in entertainment outlets and less and less time with their families.

The optimism of the 1920s was fueled by the emerging mass media empire, the advertising industry, and the corporations that marketed electric appliances, automobiles, and mass illusions. Consumer confidence had reached an all-time high. However, the new consumerist attitude led to irrational spending and overproduction, which eventually set the stage for the most severe economic depression in the history of the United States.

The 1920s witnessed the rise of consumerism and mass culture, significantly influenced by the post-World War I economic boom. This era, often referred to as the “Roaring Twenties,” saw a dramatic shift in lifestyle and social norms, particularly in the United States and Europe.

The 1920s’ rise in consumerism and mass culture set the stage for modern consumer societies, laying the groundwork for contemporary marketing, entertainment, and lifestyle trends.