Among the most persistent myths of the width and breadth of Japan’s sexual perversions is this one: visitors have claimed you could buy used schoolgirls’ panties from public vending machines, though few admit to having seen such a thing themselves. The typical story involves a friend or the guy next to the guy in the bunk across the hall in the hostel who had seen such a vending machine in the wild. But do they really exist? Can you buy used underwear in vending machines in Japan?

It seems at least possible. Japanese vending machines are amazing things. Known somewhat uncreatively just as jidohanbaiki (automatic selling machines), they are, in fact, a wonderland of products. In addition to nearly every soft drink known on planet Earth, you can also buy canned coffee, hot or cold, whole meals, crepes, fresh flowers, beer, and whiskey.

You can purchase socks and a necktie, deodorant, and shaving tackle 24/7 at a vending machine. And there are a lot of chances to buy. The country has the highest ratio of vending machines to landmass in the entire world, for a total of some 5.52 million machines. Japan’s low crime rate means they are rarely vandalized.

While there have been reports of such vending machines existing in Japan in the past, particularly in the 1990s, they are not a common or widely accepted phenomenon in Japanese culture. The Japanese government has implemented strict regulations and laws that have largely curbed the sale of such items, especially in vending machines, to address concerns over morality and legality.

Today, the presence of such vending machines is either extremely rare or non-existent. It’s important to approach this topic with an understanding of its sensationalized nature and the current legal and cultural standards in Japan.

What About Those Used Schoolgirl Panties?

It is not a question to be dismissed lightly. Japanese men are schoolgirl crazy, some weird mix of pedophilia, youth culture, and perhaps repressed desires left over from youth. Since apparently normal sex is no longer functioning well in Japan (the falling birth rate terrifies economists), most of this gets expressed through the near-infinite range of fetishes in Japan. Panties and, um, doing “stuff” with them have a huge following.

In the 1980s, young women could make serious money selling their undies to a “men’s shop.” These were even scummier places than they sounded like, often located under train tracks and in the alleys behind the back alleys. Dirty old men would roll in and make purchases. Some of the places had posted hours for the girls to sell and the men to buy so the two groups would not have to meet. Segregated shame.

The cops eventually shut all that down, finding it too gross even for Japan. Soon after, the myth that used panty selling had migrated to vending machines arose.

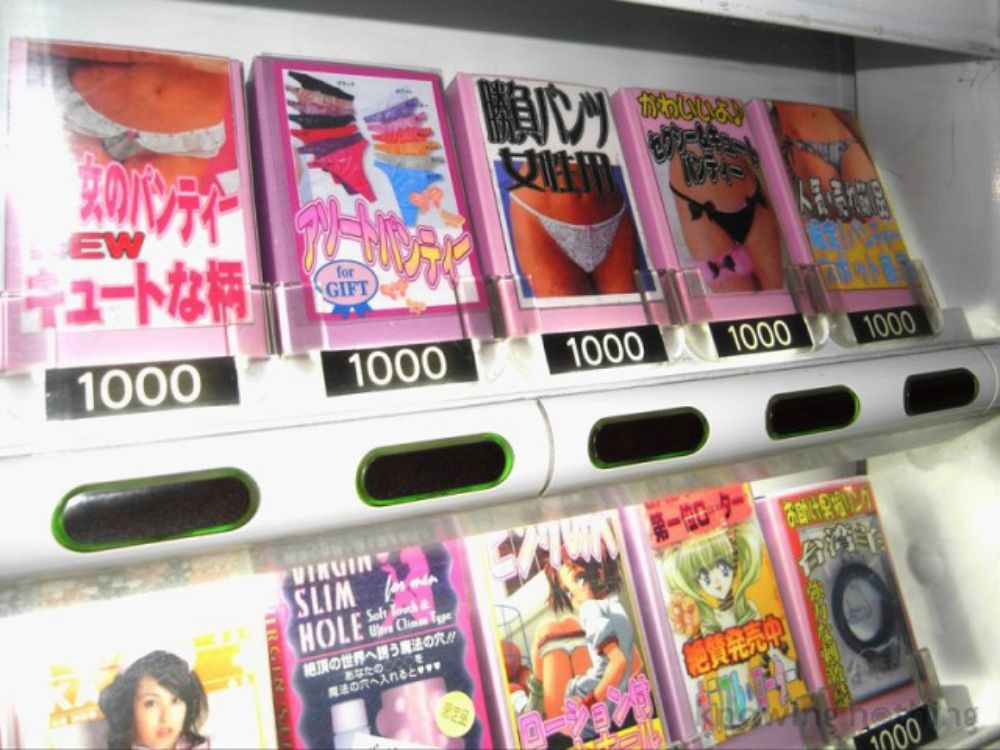

One intrepid journalist set out to answer the question once and for all. He reports that while you can indeed buy schoolgirl panties from a vending machine, they are not really “used.”

The journalist found that for about five U.S. dollars, you could purchase a pair of panties manufactured to appear used. While the Japanese text on the vending machine makes this clear enough, English words such as “used” are prominently featured to attract attention. Japanese customers instantly know the difference, while foreigners who can’t read the language return home with lurid but false tales.

Or are they?

While Japan-used underwear vending machine stories fall into the dark corners of urban myth, there appears to be a thriving online trade in selling what is said to be legitimately used women’s underwear. Purported female sellers advertise exactly how long they wore an item and often promise to include a photo of the exact item being worn.

Who can say if the goods are real or fake? But to the weird customers who buy these things, it probably doesn’t really matter.