The markers on the graves of Almond Fisher and Leonard Funk in Arlington National Cemetery have these words just below their names- “Medal of Honor”. As winners of the Congressional Medal of Honor, they have earned their final resting place in Washington, D.C. But the mere words, Medal of Honor, do not do justice to what these two brave men did to warrant the nation’s highest award for valor.

Almond Fisher and Leonard Funk demonstrated remarkable courage in the face of death, performing heroic acts during World War II that continue to inspire us today.

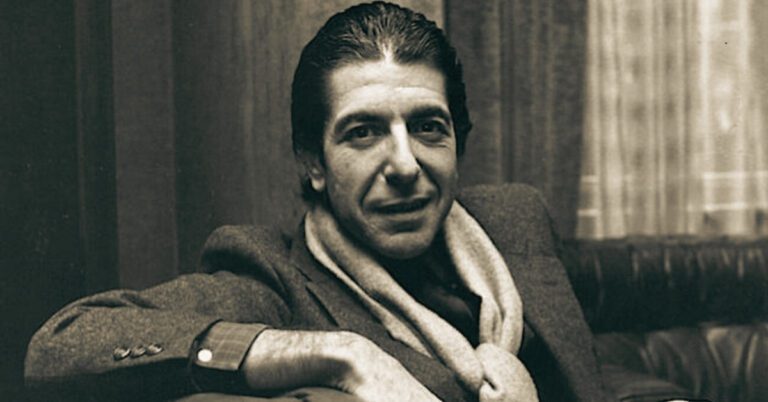

Leonard Funk

Leonard Funk was born in Braddock Township, Pennsylvania, on August 27th, 1916. He enlisted in the Army when he was twenty-one, in June of 1941.

Volunteering for airborne training, Leonard worked to get his wings; after receiving them, he was assigned to the 508th Parachute Infantry, which was sent to England as part of the 82nd Airborne Division. He survived the D-Day jump into France with the 82nd and later became part of Operation Market Garden, an attempt to secure bridges in Holland over the Rhine River from the Germans. The diminutive Funk, only five foot five, garnered a Distinguished Service Cross for the leadership of his men as they attacked a German stronghold during the operation.

As the Battle of the Bulge began in December of 1944, Funk had been promoted to First Sergeant. As the German Army tried to break through the Allies in Ardennes, the 82nd was part of the two-division force that was there to stop them.

After the Germans were halted, on January 29th, 1945, Leonard Funk performed the feats that led to his gaining the Medal of Honor. In charge of a makeshift platoon, he was given the task of assaulting fifteen German-occupied houses in Holzheim, Belgium. In a fierce snowstorm, he and his men captured a total of over eighty prisoners. The platoon was understaffed; Funk could only spare four soldiers to guard the Germans in the yard of one of the houses. He returned to the fight, but when he ran into heavy resistance, he came back for the four men, assuming that by now, other paratroopers had arrived to handle the prisoners.

What Leonard Funk did not know was that while he was gone, a German force dressed in similar white camouflaged capes as those of the Americans had surprised the four guards and freed their comrades. Funk and another soldier walked into their midst, unaware that they were now armed and preparing a counterattack.

His Tommy gun hanging over his soldier, Funk was told to drop the weapon by a German officer, who was covering him with a pistol. Faced with this prospect, Leonard Funk wheeled his gun into position and killed the officer and others in the patrol that had overpowered the Americans. The return fire left the soldier accompanying Funk dead. As Funk reloaded his weapon, the Americans who had been disarmed by the Germans grabbed up guns at Funk’s behest from the men he had just killed and joined the fight. The fray was over in less than a minute, with twenty-one Germans dead and twenty-four more wounded. The rest were taken prisoner once more.

Leonard Funk received his Congressional Medal of Honor at the White House in August of 1945. After the war ended, he returned to his job as a clerk, which he had held before he enlisted. He had also been given three Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, and a Bronze Star, in addition to his Medal of Honor and Distinguished Service Cross. He joined the Veteran’s Administration in 1947 and retired as Division Chief of the Pittsburgh office in 1972.

Leonard Funk passed away on November 20th, 1992, at the age of 76. His wife, Gertrude, survived him. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery on November 27th, in Section 35, grave 2373-4. Funk was the sole surviving Medal of Honor winner from the 82nd Airborne.

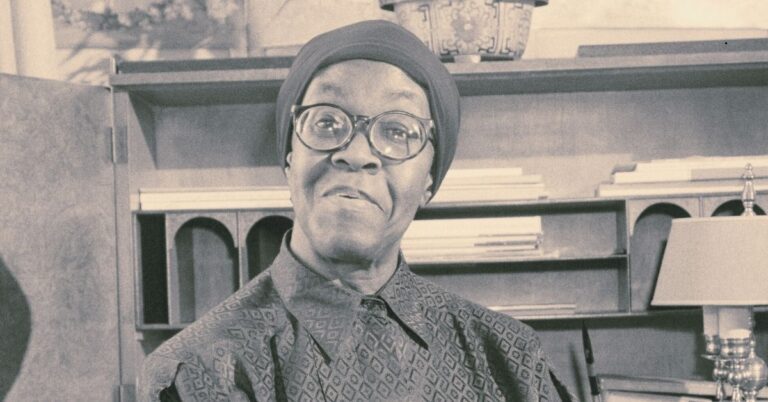

Almond Fisher

Almond Fisher hailed from Hume, New York, where he was born on January 28th, 1913. As a Second Lieutenant, he was with the 45th Infantry Division in September of 1944 near Grammont, France.

At 2:30 AM on the morning of September, Fisher was leading a platoon through the darkness against a fortified German position on a hill. When they were stopped by machine gun fire, Fisher crept within twenty feet of the machine gun nest and dispatched the crew with his carbine. Advancing, they were once again halted by machine guns. Fisher was able to wipe out this threat with grenades and his machine gun, and the platoon moved on.

Under the leadership of Almond Fisher, the platoon was able to eliminate the enemy strongholds. At one point, he shot and killed a German who had leaped from a foxhole and tried to take the rifle of one of his men. As they crossed an open field, the platoon came under fire from yet another machine gun crew.

Disregarding his own safety, Fisher made his way to the gun, without any cover from enemy fire, and destroyed it and the soldiers operating it. One more machine gun lay in their path. Fisher called for grenades, but only two were left in the whole platoon. He pulled the pins and crawled within yards of the Germans, then threw the grenades, demolishing the gun and killing the enemy. As dawn approached, he ordered his men to dig in.

Fisher had been wounded in both feet by pistol fire; unable to stand, he literally crawled from man to man, preparing them for the defense of the ground they had taken. Despite being outnumbered by the Germans, Fisher’s depleted platoon held the ground in fierce fighting, with the wounded Lieutenant encouraging his men. Only when the battle was over, and the Americans were triumphant, did Fisher crawl to the first aid station three hundred yards away to be tended to and then evacuated.

In April of 1945, Almond Fisher was awarded the Medal of Honor. He stayed in the Army, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel. He died on January 7th, 1982, at the age of 68. He is buried in Arlington in Section 6, where he, Leonard Funk, and all the others who served their country are honored by a grateful nation.