Exiles of the failed European revolutions of 1848, the Forty-Eighters, had a significant role during the American Civil War era.

After the revolutionary governments of Europe espousing liberal reforms attained power in 1848, the conservative and monarchical forces took back that power in 1849. The revolutionary leaders and their supporters escaped or immigrated to America in droves, hoping to practice and promote their ideals in a country that was undergoing a social and political crisis of its own.

What are German 48ers?

The European revolutions of 1848 were a series of interconnected uprisings across the continent, driven by widespread dissatisfaction with political, social, and economic conditions. The revolutions sought to overthrow autocratic governments and establish liberal, democratic societies. The German Revolution was particularly notable for its attempt to unify the various German states and create a democratic constitution.

One of the central events for the Forty-Eighters was the Frankfurt National Assembly, which convened in May 1848. It was the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany, tasked with creating a constitution for a unified German state. Although the assembly succeeded in drafting a constitution, it ultimately failed due to political fragmentation, lack of support from the German princes, and military intervention.

After the failure of the revolutions, many Forty-Eighters faced persecution and exile. A significant number emigrated to the United States, where they became influential in various fields. These immigrants were well-educated and politically active, contributing to the intellectual and cultural life of their new country. They were involved in promoting progressive causes such as abolitionism, labor rights, and women’s suffrage.

Republican Party

For the German-American Forty-Eighters, the best political instrument to ply their revolutionary ideals was the new Republican party. The party’s general disapproval of slavery with the immediate goal of stopping its expansion appealed to German Americans. In their eyes, the southern plantation slaveholder was essentially the same as the repressive aristocrat back in the old country.

As a result, the German Forty-Eighters became a significant voting bloc in the Republican party. Hans Reimer Claussen of Davenport, Iowa, drafted a resolution at a German Republican Club meeting on March 7, 1860, in Davenport against the presidential nomination of front-runner Edward Bates, who had ties with the anti-immigrant Know-Nothings. Consequently, other Republican organizations drafted similar resolutions. Abraham Lincoln won the nomination, and scholar Hildegard Binder Johnson concluded that the German vote could at least eliminate unacceptable candidates.

Another German Forty-Eighter, Carl Schurz, a farmer and abolitionist from Wisconsin, helped pave the way for Lincoln’s presidential victory. At first a supporter of William Seward of New York for the Republican nomination, Schurz mobilized a large part of the German-American vote for Lincoln in the general election, according to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. With Lincoln as President-Elect and slavery threatened, the southern states seceded.

U.S. Arsenal in St. Louis

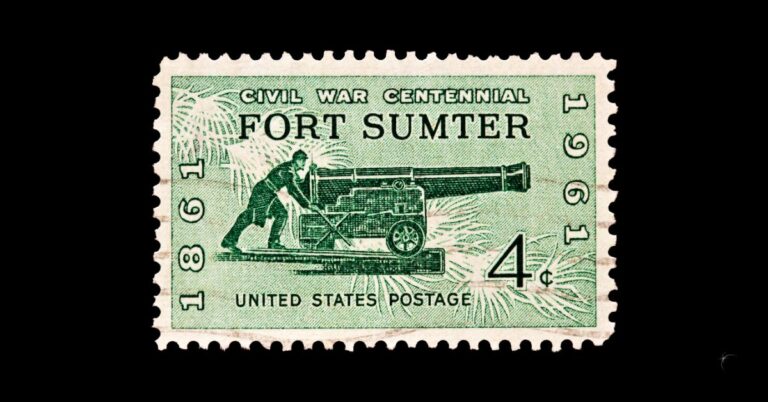

When the Civil War began in April 1861, the U.S. Arsenal in St. Louis- with 60,000 muskets, 90,000 lbs of gunpowder, 1.5 million cartridges, several dozen cannons, and machinery for arms manufacture- was lightly guarded. The German-Americans in St. Louis took the initiative, with 1400 of them organized into Home Guard regiments (mustered into federal service a short time later) led by Forty-Eighters Franz Sigel, Henry Bernstein, and Nicholas Schuettner. They guarded the arsenal and later subdued the secessionists gathered at nearby Camp Jackson without a fight. General U.S. Grant believed the Germans saved the arsenal and St. Louis from Confederate capture.

Grant also believed in another Forty-Eighter- Nicholas J. Rusch of Davenport. A former Lieutenant Governor of Iowa with a position in the commissary department of the military service, Rusch developed a plan at Vicksburg, Mississippi, to protect Union steamboats from guerilla attacks. An army of lumberjacks along the Mississippi River would supply the boats with fuel and help thwart guerillas. Grant urged the Secretary of War to approve the plan as quickly as possible.

Unfortunately, the German-American reputation as a fighter suffered during the course of the war. Schurz, who was awarded with a command by Lincoln, led German-speaking units at the Battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. His soldiers retreated pell-mell in those battles. This shouldn’t diminish the German’s ardor for the cause- they supplied approximately 750,000 of the Union’s 2.5 million soldiers, or 30%.

Lajos (Louis) Kossuth

Besides Germans, a Hungarian among the Forty-Eighters also influenced America’s conflict over slavery. Lajos Kossuth had led revolutionary forces in Hungary over the ruling Hapsburgs of Austria. After the reactionary crackdown, the exiled Kossuth arrived in America in December 1851 to a rousing welcome, seeking support for his cause. The heroic exploits of the “Noble Magyar” had been followed closely by Americans in the press.

Despite the welcome, Kossuth exacerbated sectional tensions in America. The anti-slavery crowd was mostly enthusiastic about Kossuth’s appearances. Abolitionist Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio remarked, “Every speech [Kossuth] makes is the best kind of Abolition lecture.” Only William Lloyd Garrison and his followers were disappointed in Kossuth because he didn’t outright condemn slavery.

Meanwhile, Southern leaders viewed Kossuth with suspicion. Southerners feared that Kossuth’s references to universal liberty and self-determination could encourage slave revolts. In Washington D.C., Georgia, Congressman Alexander Stephens led the successful effort to withdraw a passed resolution welcoming Kossuth to the capital. Historian Sean Wilentz surmised, “Efforts to remind Americans of the democratic political beliefs they supposedly held in common ran the risk of exposing how divided they actually were.”

Certainly, the American Civil War would have gone on without the Forty-Eighters, but the outcome might have been a bit different. The Forty-Eighters had a role in getting the Republicans and Lincoln into power. They perhaps saved St. Louis from capture, preventing the Confederates from acquiring arms and maybe control of the Mississippi River. They added extra fuel to the slavery debate in the 1850s. The Forty-Eighters may have failed in Europe, but they succeeded in America.