Howard Zinn, the “people’s” historian and social activist, was born on August 24, 1922, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of immigrant Jewish parents. His father, Edward Zinn, had emigrated to the U.S. from his native Austria-Hungary along with his brother, while his mother, Jenny, emigrated from Irkutsk, Siberia, in what was then the Russian Empire. Both parents reached the United States before the First World War, an apocalyptic event that remapped the face of Europe and brought the communist Union of Soviet Socialist Republics into being, as well as sowing the seeds of “National Socialism,” i.e., fascism. Handicapped by limited educational backgrounds, both of Zinn’s parents worked in factories when they courted and married, and the city apartments in which they raised their children were devoid of books until they subscribed, via “The New York Post,” to a 20-volume library of Charles Dickens’ collected works for 25 cents each.

Thus, the young Howard was introduced to the realm of the imagination and the world of letters under the sympathetic conscience of Dickens, the chronicler of the aspirations and desperation of the lower middle class.

During the early years of World War II, Zinn worked as a defense industry worker in the Brooklyn shipyards and became a labor union organizer. He subsequently enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force, was commissioned an officer, and was attached to a B-17 crew as a bombardier with the 490th Bomb Group that conducted bombing missions in Europe. Zinn came to question the “strategic” bombing of France and Germany, which caused millions of civilian casualties, and his repulsion with his role in the deaths of civilians as well as German soldiers who were ready to surrender but had been marked as targets by the U.S. military brass made him come to question the morality of modern warfare.

In April 1945, Zinn’s crew participated in the fire-bombing of Royan, France, the first time napalm (essentially jellied gasoline) was used in warfare. The bombings were aimed at German soldiers who were, in Zinn’s words, hiding and waiting out the closing days of the war. The attacks killed not only the German soldiers but French civilians as well. Nine years later, Zinn visited Royan to examine documents and interview residents. Zinn concluded that the bombing was ordered by decision-makers for career advancement rather than for any legitimate military objective, as well as being part of the dynamics of the military system as an enterprise. Once the Army Air Force had napalm, it was going to use it, just as the military used the atomic bombs on Japan. Not using the bombs would go against the system.

After being demobilized, Zinn attended New York University on the G.I. Bill, one of the great achievements of the Roosevelt-Truman administration’s New Deal/Fair Deal social program. Zinn graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from NYU in 1951. The following year, he received his Master of Arts degree from Columbia University, where he also earned his Ph.D. in history with a minor in political science in 1958. His doctoral dissertation, LaGuardia in Congress, a study of the career of populist Republican Fiorello LaGuardia in the U.S. House of Representatives representing the Congressional district that encapsulated East Harlem, was published by the Cornell University Press and was his first of 20 books. To Zinn, LaGuardia was a progressive, “the conscience of the twenties,” who fought to emancipate and empower the common people. As part of his social agenda, LaGuardia fought to give workers the right to organize in labor unions and to strike and also sought redistribution of wealth by progressive taxation. Zinn’s book concluded that LaGuardia’s legislative program “was an astonishingly accurate preview of the New Deal.”

In 1956, Zinn was appointed chairman of the Department of History and Social Sciences at Spelman College, a women’s college in Atlanta, Georgia, that served African American women. The sister institution to traditionally black Morehouse College, Zinn joined the faculty at a time when, after nearly 100 years of defacto segregation, the nearly 60 years of de jure segregation had recently been declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. The home of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (who attended Morehouse College, where he was mentored by the school’s president, civil rights leader Benjamin Mays; King received his Ph.D. from Boston University in 1955), Atlanta was one of the centers of the modern Civil Rights movement, and many of his students became involved in pushing for an end to segregation and for equality under the law for African Americans.

Zinn has recollected that he began to question the traditional interpretations of American history when he was required to teach his African American students from books that ignored the true experiences of black folk in America. He realized that the “official” histories of the United States during that Cold War period had little connection to the reality of life as lived by ordinary people in the United States. This can be contrasted to the propaganda about what would later become known as “The Good War,” which obfuscated the actual conduct of the Allies during World War II, a time when the Allied chiefs of staff planning the air war were aware that they were committing what would be considered prosecutable war crimes if the other side had won the ear. The dichotomy between wartime propaganda and reality could not have been lost on Zinn. The truth of the firebombing of Dresden, an open city, during the waning days of World War II, an attack which cost tens of thousands of German civilians their lives, was suppressed for a generation after the War and was not widely known until the publication of Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five, which used the raid as a background.

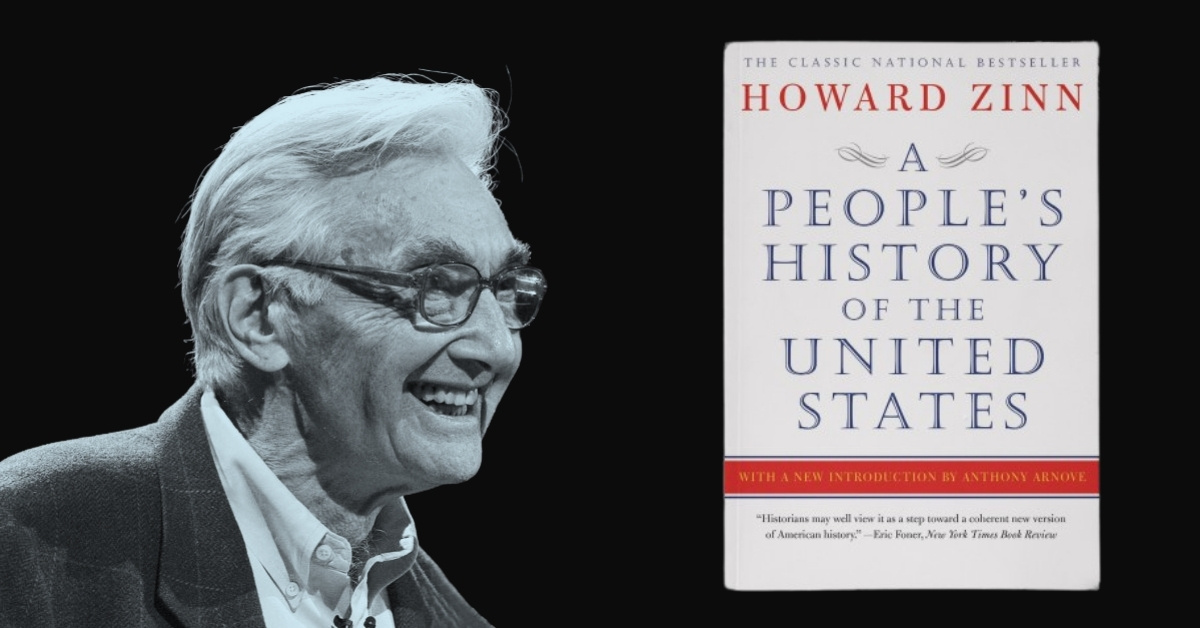

His time at Spelman radicalized him as he sought a way to reach his student body with the truth. This led to changes in his own thinking. As it developed, Zinn’s philosophy incorporated ideas from anarchism, Marxism, socialism, and social democracy. This quest for articulating what the truth was, as opposed to the consensual “reality” dictated by the white, liberal (in the economic sense of the word), conservative elites who determined what “History” with a capital “H” was, would reach its fruition with his 1980 book A People’s History of the United States, which tried to balance the dominant historical picture by focusing on the plight of the disenfranchised. However, this lay in the future.

Zinn’s intellectual and spiritual development would transform him into one of the many radical and progressive historians and intellectuals who began to give voice to those who were not heard from in official historiographies: members of minority groups and other oppressed peoples, including women. As Zinn has pointed out to his classes, “American History” likes to tell the story of the Boston Massacre, with the African American Crispus Attucks out front (albeit being gunned down by trigger-happy troops two centuries before Kent State), and how the British troops were exonerated in a great victory for the “Rule of the Law” with the counsel of future patriot/President/semi-divine “Founding Father” John Adams, but ignores the fact that in the years before the Massacre, there were frequent bread riots in Boston. That there was, in fact, in a land of plenty and great commerce, there was a great mass of poor and disenfranchised, then as now. There had been a history of class warfare in America, which the War of Independence was part of then as well as now.

Zinn would join that strain of intellectual thinking, hearkening back to Charles Beard and his An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution, a school that was suppressed during the two Red Scares that the United States had undergone, most recently with the reactionary McCarthyism of the 1950s. In the 1950s, after the works of Marx and Lenin were taken off library shelves as representing a “clear and present danger,” after the Vinson Court upheld the conviction of Communist Party USA members, Congress passed the legislative package “Education for Democracy.”

To counter the so-called communist/socialistic/New Dealer menace to businessmen and the morals of comic book-loving children (a particular bête noire of 1956 Democratic Vice Presidential candidate Estes Kefauver, despite his and young proto-juvenile delinquents’ similar taste’ in coonskin headgear), the curriculum of U.S. schools would be regulated by the federal government.

The values of “Democracy”, i.e., free market capitalism, would be extolled. The world of Sinclair Lewis’ George Babbitt and Eisenhower’s Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson’s “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country” would reign. After all, wasn’t it Babbitt who thought that his daughter’s boyfriend was a communist as he did not own a car?

The realtor who believes his success at business is virtue itself? The embodiment of Silent Cal “Keep Cool With Coolidge” Coolidge’s bromide “The business of America is business”? American History would be taught as the triumph of American pluck and courage, as in a Horatio Alger novel. History is approved by businessmen who equate commercial success and business savvy with an understanding of the world at large.

It was against these state-mandated fairy tales that intellectuals like Zinn toiled. A country lives, psychologically, on its myths, and the United States myth was that the country was exceptional, a veritable New Jerusalem among nations, unmatched by any other country (notwithstanding the fact that neighboring Canada was democratic and had the same standard of living and a better social security system).

The official myth was that the United States was unique in that it had the oldest written Constitution in the world (the United Kingdom’s constitution was older, but many an American librarian has been tormented with being asked for a copy of the document as it is unwritten; Switzerland had been a republic for 300 years before there was United States), a “Living Document” that was the summit of perfection when it came to such instruments of government, handed down as it was by a Group of Lawmakers known as the Founding Fathers who were uniquely wise and touched by the hand of the Great God Jehovah.

A perfect Union, made more perfect by the War Between the States, which forced the U.S. to truly live up to the words of the Declaration of Independence, that all men were created free, but with justice towards all coming with the end of Reconstruction and the end of the demonization of the white Bourbon landowners and their allies in the South, who had fought, died, and lived for the “Noble Cause” of the Confederacy.

The reality of American history was that the U.S. Constitution was a compromise hammered out between land-owning and mercantile elites of various regions that weighted the Congressional power towards the agrarian Bourbon aristocracy of the South by having slaves counted as 3/5th of a “person” for apportioning the seats in the House.

The truth was that rather than promoting democracy, the U.S. Constitution hamstrung it, with a pro-slavery formula for apportioning the House (which resulted in the Southern candidate winning 10 of the first 12 presidential elections) and incredibly high hurdles to amending the document. (As Gary Wills pointed out in his 2003 book on the Founding Fathers, “The Negro President,” blacks did have a “right” to vote, but that vote was controlled by the Southern planter aristocracy, a patrician class that still was in power during the 1950s and ’60s when Zinn taught at Spellman).

The high hurdle to amend the Constitution was portrayed by consensual American history as a bulwark of “stability,” which ignored the instability the system caused, i.e., the Republican victory in the 1860 presidential election representing a de facto coup d’etat against the Constitution, as Lincoln and what would become known as the Grand Old Party had pledged itself to extralegally overturning the Dredd Scott decision. From this landmark of “stability,” the bloodiest conflict America had ever been involved in was unleashed, and the lack of democracy (the Senate and “rotten boroughs” in state governments, was not addressed until the Warren Court’s 1962 Baker v. Carr decision) had hamstrung progressive legislation on equal rights and labor issues for generations.

American History ignored the threatened succession of New England over the War of 1812 (as it ignored the fact that the War was a defeat for the U.S.; the union was portrayed, until after the loss of the Vietnam War, as having an unblemished military record), the attempted succession of South Carolina over the tariff of abominations of 1832 that underscored deeper problems between the States than normally admitted to; the illegal imperialist war against Mexico of 1848; the extirpation of three-quarters of a million Filipinos after the Spanish-American War; and the legal legerdemain behind the disenfranchisement of the American Indian.

Consensus, liberal historians like Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., in his Pulitzer-Prize winning The Age of Jackson, had envisioned the past as something like the present, with Jackson and his “democratic” platform being the approximate of FDR and the New Deal. While the past was like the present, it was not in the ways the liberal historians assumed, as they created their own countervailing mythology. The reality of U.S. History was that Jackson, by destroying the Second Bank of the United States, obviated the federal government’s regulatory powers, giving rise to an oligarchy, Robber Barons, who not only plundered the wealth of the country and oppressed the disenfranchised but who de facto determined U.S. economic policy.

American history was messier than the federal government-mandated Triumph of Progress ideology would have it. With Supreme Courts that were more reactionary than not, even the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by the denigrated Radical Republicans (a populist movement), designed to protect the rights of the African American freedmen, was turned into a “Declaration of the Rights of Corporations,” that corporations were “individuals” with rights that could not be abridged by the federal, state or local governments. This became Occam’s Razor that would cut away the minimum wage and hours laws of the Progressive Era, an era that went down in flames, along with the Socialist Party and the hundreds of elected socialist officials across the U.S., with the first Red Scare of the World War One era.

At Spelman, Zinn mentored young student activists, among them future Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Alice Walker. He served as an adviser to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the main groups pushing for civil rights in the 1960s. Zinn has frequently written about the struggle for civil rights, both as a participant and historian, taking a one-year sabbatical from teaching to write his book SNCC: The New Abolitionists and The Southern Mystique. He said that while at Spelman, he observed 30 violations of the rights of students under the First and Fourteenth Amendments rights in protests in Atlanta. The police abridged the student protesters’ freedoms of speech, assembly, and equal protection under the laws.

Despite being a tenured professor, Zinn was dismissed in June 1963 after siding with students in their desire to challenge Spelman’s traditional emphasis of turning out “young ladies.” Many of the Spellman students were involved in civil rights protests, and Zinn, of course, was encouraging this venue of political expression. Zinn said that his seven years at Spelman College “are probably the most interesting, exciting, most educational years for me. I learned more from my students than my students learned from me.”

In 1964, Zinn joined the political science faculty at Boston University, where he taught until 1988 and where he currently maintains an office as professor emeritus. B.U.’s political science department, at one time in the late 1970s, was reported to have more Marxists as tenured professors than any other American university. Whether that was true or not, Zinn joined a department that was dominated by progressives and leftists.

It was during his first decade at B.U. that Zinn became known as a vocal critic of war, particularly the Vietnam War. Zinn later said his experience as a bombardier sensitized him to the ethical dilemmas faced by G.I. during wartime. Zinn questioned the justifications for military operations inflicting civilian casualties in the Allied bombing during World War II. Zinn’s thoughts were highly relevant in the 1960s as the U.S. armed forces, under President Lyndon Johnson, were trying to bring North Vietnam to heel through a massive bombing program that claimed hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of civilian lives during the Johnson and Nixon administrations.

The great irony of the bombing was that post-World War Two studies showed that it had likely done little to hasten the end of the war. This was certainly a sobering thought for men like Zinn, who had killed millions of civilians as part of the massive bombing campaign. If the bombing campaign did little to break German resistance, what was the justification for bombing North Vietnam? (During the Vietnam War, the U.S. Air Force dropped more tons of bombs on North Vietnam than it had on Germany during World War II. It would only serve to prolong the time before North Vietnam and its communist allies in the South would claim victory over the South Vietnamese military and government.) Zinn came to the conclusion that warfare was long and that nonviolent resistance was the answer to aggression. In order to facilitate North Vietnam’s offer to return three American airmen who were prisoners of war (the first American POWs released by the North Vietnamese), Zinn and prominent anti-war activist Father Daniel Berrigan visited Hanoi just before the outbreak of the Tet Offensive in late January 1968. The North Vietnamese released the POWs to Zinn and Ellsberg, who released them, in turn, to American officials.

Boston University became known as “Berkeley East” during the late 1960s and early 1970s as student protests against the War multiplied. Howard Zinn was there with the students at their protests as a mentor and participant. Due to the protests, the 1970 commencement and graduation had to be canceled. The Board of Trustees replaced the president of B.U. with the man who would become Zinn’s nemesis, former University of Texas, Austin College of Arts & Sciences Dean John R. Silber. The new president would take a hard line against student protests and an even harder line against Zinn, whose philosophy was diametrically opposed to the authoritarian Silber.

Silber, famed in academia for being one of the first drivers in the new paradigm of the university as a corporation serving the business world, not only attempted to curb the academic freedom of the student body but also that of its full-time faculty. He tried to limit faculty governance of their departments, vetoing tenure and salary recommendations and forbidding the hiring of professors whose views he disagreed with, such as the famous Herbert Marcuse, whom the political science department was not allowed to hire in the early ’70s. Silber frequently clashed with Zinn, who was dedicated to intellectual, personal, and political freedom.

Zinn was involved in one of the seminal moments in the domestic opposition to the Vietnam War, The Pentagon Papers case. RAND consultant Daniel Ellsberg had secretly copied a RAND study describing the internal planning and policy decisions of the Pentagon during the Vietnam War, a study commissioned by the federal government, which classified it as TOP SECRET. After Ellsberg gave him a copy of the report for safekeeping, Zinn, his wife Roslyn, and his friend Noam Chomsky (then mostly known as a professor of linguistics at M.I.T.) edited and annotated the copy that Ellsberg entrusted to him. Zinn’s publishing house, the Beacon Press, published what has come to be known as the Senator Gravel edition of The Pentagon Papers, four volumes of Pentagon documents plus a fifth containing an analysis by Zinn and Chomsky.

Zinn was called by the defense as an expert witness at Ellsberg’s criminal trial for conspiracy and espionage in connection with the publication of the “Pentagon Papers” by the country’s paper of record, “The New York Times.” Taking the witness stand for several hours, Zinn discussed the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam from World War II to 1963.

“I explained there was nothing in the papers of military significance that could be used to harm the defense of the United States,” Zinn later wrote about his experience as a defense witness, “that the information in them was simply embarrassing to our government because what was revealed, in the government’s own interoffice memos, was how it had lied to the American public. The secrets disclosed in the Pentagon Papers might embarrass politicians and might hurt the profits of corporations wanting tin, rubber, and oil in far-off places. But this was not the same as hurting the nation, the people.“

Most of the jurors later said that they would have voted for acquittal, but the federal judge hearing the case dismissed it on the grounds that it had been prejudiced by the burglary of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office under the direction of the Nixon administration.

As a historian, Zinn – dismayed by the point of view expressed in traditional history books – published his most famous work (and a watershed in American historiography), A People’s History of the United States, in 1980 to provide other perspectives on American history.

The text depicts the struggles of Native Americans against the European and American conquests of their land, of slaves against slavery, of unionists and labor against capitalists, of women against patriarchy, of allegedly “free” African Americans against racism and for civil rights, and of others who were disenfranchised and whose stories are not often told in mainstream histories. A classic of populist history, A People’s History, has been assigned reading as both a high school and college textbook. The most widely known example of critical pedagogy, A People’s History, sold its one-millionth copy in 2003.

Howard Zinn currently resides in the Boston suburb of Newton, Massachusetts, with his wife Roslyn, an artist and editor who has had a role in editing all of Zinn’s books. The couple have two children, Myla and Jeff, and five grandchildren. Roslyn is In addition to his history, Zinn has become an accomplished playwright. His first play, Daughter of Venus, was produced in 1985, and his most famous play, Emma, based on the life of anarchist Emma Goldman, has been staged five times since its initial production as The Radical Vision EMMA by the M.T.A/Paul Leavin at New York City’s Tomi Theater in 1986. His most recent play is Marx in Soho, a drama with Karl Marx as a character that considers the meaning of history. Marx in Soho has been continuously performed in small theaters throughout the United States since 1999.

At a time when a U.S. President, ignoring Georges Santayana’s dictum that “Those who do not know history are forced to repeat it,” has gotten us into another Vietnam-like war in the Middle East and has tried to reduce the purview of the First Amendment as part of the “War on Terror,” Howard Zinn is as relevant as ever. As a historian and political philosopher, he remains an important voice of reason. Indeed, he has become the conscience of his country. The United States is better because of it.