In any worthwhile American phrase book, you should be able to find “This ain’t my first rodeo.” It means, “I’ve done this before” or “I am quite experienced.” Of course, if you took the average American to a rodeo, it would be his or her first time.

According to The Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA), headquartered in Colorado Springs, Colorado, there are 35 million self-identified rodeo fans in America, about 11% of the population.

The good people at the PRCA state, “According to the Sports Business Daily, rodeo is seventh in overall attendance for major sporting events, ahead of golf and tennis. Fans can follow professional rodeo all year long through the PRCA’s television coverage on CBS Sports Network, the PRCA’s ProRodeo Sports News magazine, and ProRodeo.com, as well as other rodeo-related media outlets.”

The PRCA also says, “The PRCA’s 5.4 million loyal rodeo attendees across the U.S. are about 49 percent male and 51 percent female; 51 percent have a household income of $50,000 or more, and 70 percent own their own homes. ProRodeo fans come from all walks of life, but as a group, they are demographically similar to NASCAR fans and are likely to enjoy hunting, fishing, and camping.”

What is a Rodeo

The roots of rodeo (pronounced like “radio” replacing the “a” with an “o” – not ro-DAY-o as in Spanish, or as in the high-priced shopping street in Beverley Hills, Rodeo Drive) go back probably to the domestication of livestock. The sport grew alongside the cattle industry’s development in Spanish America and later in the Southwestern US.

The Texas State Historical Association says, “Rodeo is a sport that grew out of the cattle industry in the American West. Its roots reach back to the sixteenth century. The Spanish conquistadors and Spanish-Mexican settlers played a key role in the origin of rodeo with the introduction and propagation of horses and cattle in the Southwest.”

After the Civil War, with the abundance of wild cattle in the Southwest and a market in the East, the era of cattle drives, large ranches, and range cowboys began. Skills of the range cowboy led to competitive contests that eventually resulted in standard events for the rodeo.

With its roots deep in Southwest history, rodeo continued to evolve until it has become a professional sport for men and women that youth rodeo organizations are perpetuating.”

Yes, there is such a thing as a professional rodeo cowboy (and cowgirl since founding the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association in 1948 ). They don’t make the ridiculous sums football, baseball, and basketball players make. “The total payout at PRCA rodeos in 2014 was $41,102,501.”

The PRCA is the richest of the associations, so you can see that you rarely get rich this way.

The financial structure has a lot to do with this. Unlike most other professional sports, where contestants are paid salaries regardless of how well they do at a particular competition, cowboys generally pay to enter each rodeo. If they place high enough to win money, they probably profit, but if they don’t, they lose their entry fee and travel expenses. Hence, every entry is a gamble pitting the chance for loss and physical injury against the chance for financial windfall and athletic glory.

So, to understand what the modern-day rodeo is all about, let’s suppose, for the sake of argument, that you want to be a professional cowboy/girl.

First off, you probably want to decide on your event or events. Seven events are pretty standard in professional rodeo. These seven are split into two groups: timed and rough stock events. The difference is in how these two classes are scored. Timed events are exactly what they sound like; the idea is to post the fastest time.

Roughstock is judged, not unlike gymnastics, diving, or figure skating; two judges each rate the performance of the cowboy or cowgirl on a scale of 0-25. They also rate the performance of the animal from 0-25. The four scores are combined to determine how a rider did.

Now, why do they score the animal? Well, if you take an old horse about ready to be sent to the glue factory and put me on it, even I might be able to stay on for the 8 seconds required. Get a horse who is feeling rambunctious, and even the toughest cowboys face a difficult ride. By scoring the animals, the rodeo has made allowance for the different tempers of the animals.

The timed events you usually see at a rodeo are:

Barrel Racing

This event is a horse race with turns. The cowgirl’s time begins as she rides her horse across the starting line in the arena. She runs around three upright barrels in a cloverleaf pattern and back to the starting line where the clock stops. Tipping a barrel is permitted, but a five-second penalty is added to her time if it is knocked to the ground.

Calf Roping

Calf roping is an authentic ranch skill that originated from working cowboys. Once the calf has been roped, the cowboy dismounts and runs down the length of the rope to the calf. When the calf is on the ground, the cowboy ties three legs together with a six-foot pigging string. Calves are given a head start, and if the cowboy’s horse leaves the box too soon, a barrier breaks and a 10-second penalty is added to the roper’s time. In all the timed events, a fraction of a second makes the difference between winning and losing.

Steer Wrestling

This event was originally called “bulldogging” and requires the cowboy to lean from the running horse onto the back of a 600-pound steer, catch it behind the horns, stop the steer’s forward momentum, and wrestle it to the ground with all four of its legs and head pointing the same direction. The bulldogger is assisted by the hazer, who rides along the steer’s right to keep the animal running straight.

Team Roping

Team roping is the only rodeo event that features two contestants. The team is made up of a header and a heeler. The header ropes the horns, then dallies or wraps his rope around his saddle horn and turns the steer to the left for the other cowboy who ropes the heels. The heeler must throw a loop precisely to catch both of the steer’s hind legs. The time clock stops once both ropers have made a catch and brought the animals to a stop, facing each other.

The rough stock events are:

Bareback Bronc Riding

The event is judged according to the performances of both the rider and the bucking horse. It is a single-handhold, eight-second ride that starts with the cowboy’s feet held in a position over the break of the horse’s shoulders until the horse’s front feet touch the ground first jump out of the chute. The rider earns points for maintaining upper body control while moving his feet in a toes-turned-out rhythmic motion in time with the horse’s bucking action.

Saddle Bronc Riding

Known as rodeo’s classic event, saddle bronc riding is judged similarly to bareback bronc riding. However, there are additional possibilities for being disqualified: losing a stirrup or dropping the thickly braided rein attached to the horse’s halter. The cowboy sits on the horse differently due to the saddle and rein, and the spurring motion covers a different area of the horse. Saddle broncs are usually several hundred pounds heavier than bareback horses and generally buck slower.

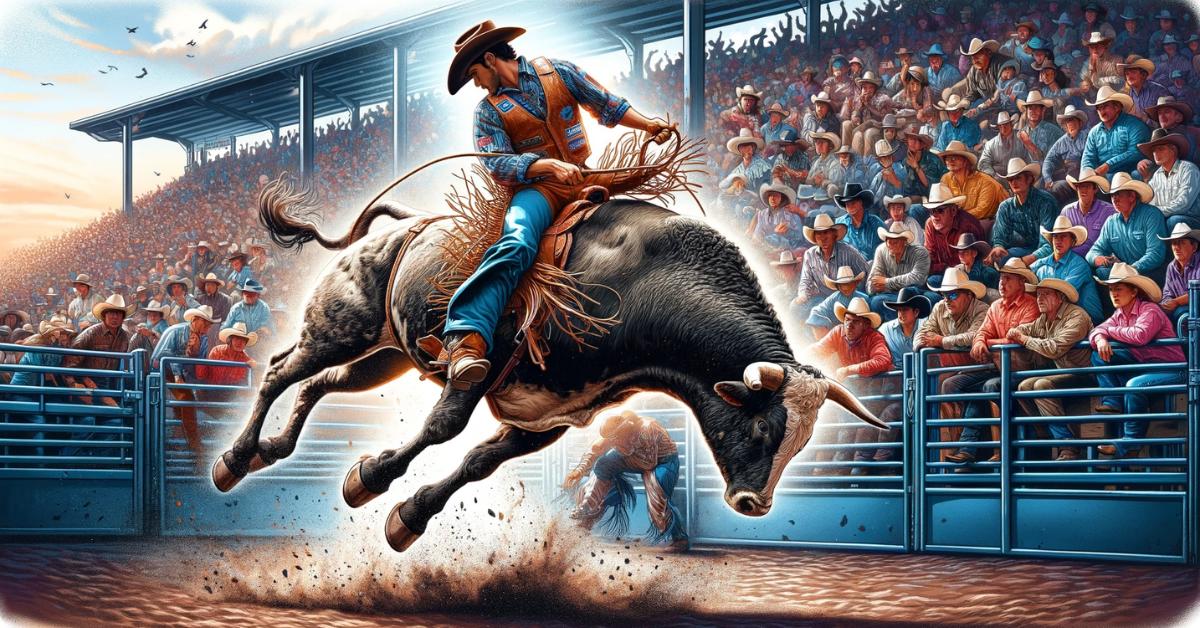

Bull Riding

Bull riders, who might not weigh more than 150 pounds, place a flat braided rope around a bull that weighs almost 2000 pounds. The bull rope is placed around the animal, just behind its shoulders. It is then looped and threaded through itself, and the cowboy wraps it around his riding hand with only his grip holding him in place. The rider relies on balance and leg strength to make the eight-second buzzer. Look for bull riders to sit up close to their bull ropes and to turn their toes out because rides are judged on the riding style of the competitor and the bucking ability of the bull.

The Professional Bull Riders, Inc

Bull Riding has an independent circuit, the Professional Bull Riders, Inc., known as the PBR.

Headquartered in Colo, the Professional Bull Riders, Inc. was created in 1992 when a group of 20 visionary bull riders broke away from the traditional rodeo scene, seeking mainstream attention for the sport of professional bull riding. They felt that, as the most popular event at a rodeo, bull riding deserved to be in the limelight and could easily stand alone. Each rider invested a hard-earned $1,000, a few of them borrowing from family and friends, to start the PBR.

How successful is the PBR? Last weekend, the cowboys rode their bulls at Madison Square Garden in New York City in the Built Ford Tough Series.

Some rodeos offer different events. For instance, the 101 Wild West Rodeo in Ponca City, Oklahoma, offered single mugging (tying a calf down by three legs) and wild cow milking.

So, you have decided on your event and are ready to become a professional rodeo cowboy or cowgirl. You now need to get yourself a permit card.

A cowboy who wishes to become a member of the PRCA must first apply for a permit. The PRCA entry fee for permit application costs $300. Anyone of legal age can enter to become a permit holder and gain access to many of the contests. The legal age is based on the state in which the cowboy lives. If the age of majority is over 18, then that legal age is applied to the applicant.

The potential permit member must complete an application signed before a notary public and mailed with their social security number or tax number. Applications cannot be submitted electronically. Membership lasts from January 1st until December 31st each year, and dues are accepted for the following year starting in September.

Once you have your permit, you can participate in PRCA-sanctioned rodeos.

The next step in your development as a professional rodeo cowboy is to win $1,000 or more in aggregate at sanctioned rodeos with your new permit. Once you have earned that much (and there is no time limit), you become eligible to be a card-holding PRCA contestant. While a permit holder, your winnings count toward your circuit standings (local) but not toward world or rookie standings (first-year cardholders). When you get your card, these winnings count at all levels.

This is similar if you are familiar with how professional golf operates under its touring card system.

Rodeo And Its Conflict With Animal Rights Groups

Rodeo has, almost by its very nature, upset various animal rights groups. The argument that a steer probably doesn’t want to be wrestled is tough to dispute. The PRCA has a section on its website that addresses this – with a political slant.

An important distinction to make when dealing with animal issues is the difference between animal welfare and animal rights. After learning the difference between the two philosophies, it is easier to distinguish between organizations that directly help animals and those that wish to end the use of animals.

Animal Welfare – based on principles of humane care and use. Organizations that support animal welfare principles seek to improve the treatment and well-being of animals. Supporting animal welfare premises means believing humans have the right to use animals, but along with that right comes the responsibility to provide proper and humane care and treatment.

Animal Rights – organizations that support animal rights philosophies seek to end the use and ownership of animals. Animal rights organizations seek to abolish by law the raising of farm animals for food and clothing, rodeos, circuses, zoos, hunting, trapping, fishing, the use of animals in lifesaving biomedical research, the use of animals in education, and the breeding of pets.

The PRCA has more than 60 rules governing the treatment of the animals.

Interestingly, there are also standings for the bulls and the contractors who provide them as part of the PBR. “The Professional Bull Riders, Inc. uses over 70 stock contractors across the United States. On average, a stock contractor owns 20 to 200 bulls. The PBR has set high standards for each stock contractor and their bucking bulls. These bulls need to maintain a certain caliber to ensure that they are in top-notch shape to perform. PBR Livestock Director Cody Lambert travels nationwide and hand-picks PBR bulls for each Built Ford Tough Series event”.

At any given event, as many as eight to 15 different stock contractors are represented, who are selected based on the locale and, more importantly, the quality of their stock. Each contractor supplies approximately seven to eight bulls per event. The bulls arrive at least 24 hours before an event, which helps guarantee that the bulls are acclimated, rested, well-fed, and hydrated before the competition.

Finally, as America becomes increasingly urban, you might think rodeo’s future is uncertain. The fact is that the PRCA has established a Youth Rodeo program to develop the future stars of rodeo. In particular, the organization has set up a network of youth rodeo camps.

Our mission is to provide a fun, positive rodeo experience. The camp curriculum includes an introduction to rough stock events emphasizing safety, fundamentals, chute procedures, livestock safety, an overview of riding equipment, injury prevention, management, fitness, and nutrition, an introduction to PRCA business, and goal-setting. Instructors encourage participants as they pursue their rodeo careers and educational endeavors.

During its inaugural year, this nationwide program hosted camps in five cities. Camps provide free learning opportunities for cowboys who have had little or no direction in rodeo or have been competing in rodeo and want to learn about the fundamentals from PRCA champions further.

This program has been made possible through the generous contributions of PRCA members and rodeo committees who have donated their time, talents, and resources to this new program. Donations have included arenas, livestock, meals, and travel costs.