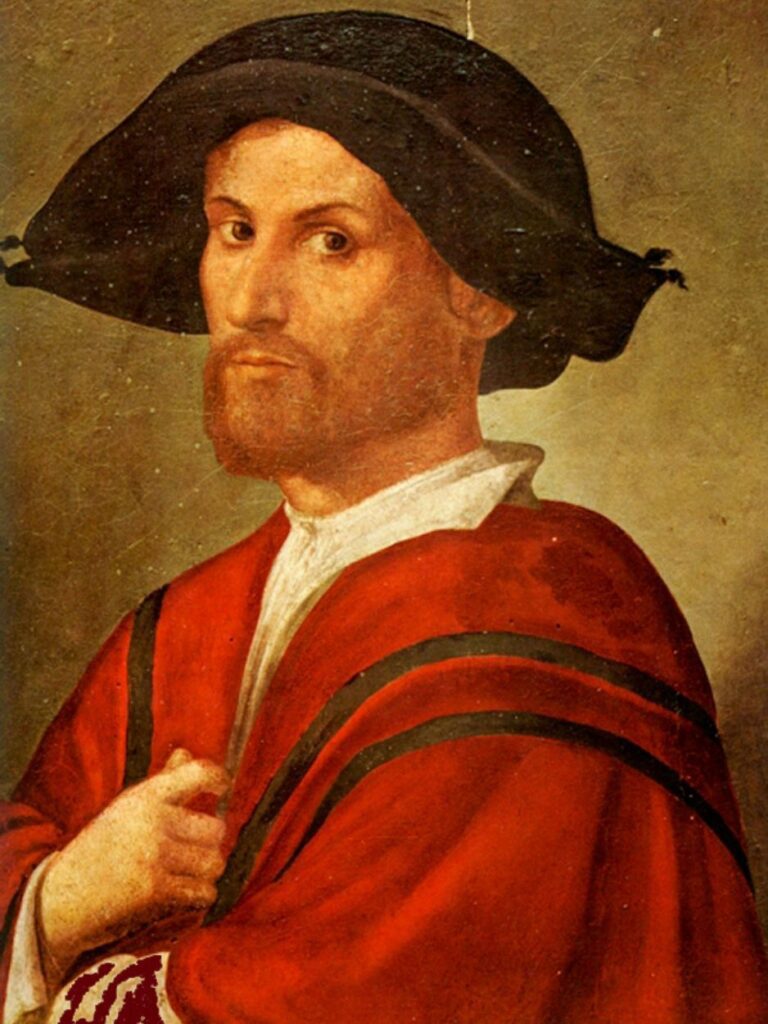

Juan Borgia was the spoiled, arrogant favorite son of Rodrigo Borgia, aka Pope Alexander VI. But his father’s ambitions for him led to his death in 1497.

In 1488, 11-year-old Juan was gifted the Duchy of Ganda, the Borgia family estate in Spain, by his half-brother Pedro Luis. Juan’s elder brother Cesare, aged 13, was infuriated to find himself passed over for the sake of a pampered sibling, so much so that he swore to kill Juan.

A Debauched Lifestyle

Once installed in Gandia, Juan soon proved to be a chip off the dissolute Borgia block. He spent his nights in taverns, drinking, gambling, consorting with prostitutes, and living in considerable luxury. What Juan failed to understand about Spain was that such opulence was unwelcome in a country that favored ascetic Christianity and regarded the luxuriant splendors of Renaissance Italy with disdain.

A while later, in 1497, it became clear that Juan had roused some very serious enmities. “A very mean young man,” was how one contemporary described him, “full of false ideas of grandeur and bad thoughts, haughty, cruel and unreasonable.”

Late in the summer of 1496, Juan arrived in Rome to be installed by his father as Captain-General of the Church. This was a highly prestigious post that placed Juan in charge of the papal army, even though he had no military experience, training, or talent for the task.

Infuriated Roman Nobles

There were better qualified, more deserving nobles in Rome who were far more suited to the role, and, naturally enough, they were furious at being upstaged by a callow, overindulged youth. Even so, Pope Alexander failed to understand their fury. Blinded by the inordinate love of his son, the Pope persuaded himself that the nobles’ hostility was due to jealousy of Juan and set about planning new honors for him.

One of his ideas was to make Juan King of Naples after the incumbent, Ferrante II, died in 1496. It was only when threatening noises from King Ferdinand of Aragon reached him that Alexander backed off.

Yet favoring Juan did not account for all of Alexander’s ambitions at this time. He also aimed to use his son as a means of expanding Borgia’s power in Italy. As Pope, Alexander already controlled the Papal States and planned to use papal cities within the Neapolitan boundaries – Benevento, Terracina, and Pontecorvo – to make a sizeable new territory for Juan.

When this was announced, Alexander’s enemies soon guessed its significance: it was a preliminary move to absorb Naples by more furtive means. There was, though, a terrible method by which Alexander – and Juan – could be thwarted.

A Dinner in Honor of Juan

On the evening of June 14, 1497, Juan’s mother, Vannozza, held a special dinner at her country villa near Rome to celebrate the honors that were being heaped upon her son.

Juan’s elder brother Cesare was there, together with another brother, Jofre, his wife Sancia, and their cousin, Cardinal Juan Borgia-Lanzel. The environs of Rome could be dangerous at night for such wealthy people, who could easily fall prey to marauders, so the party broke up around dusk, and Juan rode off with Cesare and a group of friends and their servants.

Somewhere along the way, Juan parted company with the others and rode on with two companions, heading for the Castel Sant’Angelo. Juan never got there, nor was he ever seen alive again.

Juan Borgia Disappears

When it was discovered that he was missing, search parties 300-strong were sent out to comb the route Juan had taken. They found nothing. Pope Alexander ordered his Spanish guards to make a fingertip search of the city. They found the groom who had accompanied Juan, but he was so badly beaten up that he could tell them nothing about the fate of his master.

They also found Juan’s horse. The animal’s trappings, particularly the stirrups, showed clear signs of a violent struggle. Still, Juan was nowhere to be found, and the Borgia guards began bullying householders to betray what, if anything, they knew about the missing duke.

What a Witness Saw

Then, at last, an eyewitness was located. Giorgio Schiavi, a timber merchant who unloaded his wood on an island in the River Tiber, revealed that around two o’clock in the morning, he had seen two men, acting furtively, throw a body into the water.

The searchers dragged the river all night, and for half the following day until, at noon, a corpse clad in rich brocade and carrying the insignia of Captain-General of the Church was discovered.

It was Juan. He was brutally hacked about as many as eight times, and his throat was cut. His hands were tied together, and a stone had been hung about his neck to make sure he sank to the bottom of the river.

The Grief of Pope Alexander

Pope Alexander was devastated when he heard how horribly Juan had been killed. It was said that he “let out a great roar like an injured animal when he saw Juan’s bloated, muddied body.”

Alexander shut himself away in the Castel Sant’Angelo and refused to let anyone in for several hours. He neither ate nor drank anything for more than three days. In his overwhelming grief, he imagined that Juan had been killed because of his own sinful excesses.

“God has done this perhaps for some sin of ours and not because he deserved such a cruel death,” he cried. “We are determined henceforth to see to our own reform and that of the church. We wish to renounce all nepotism. We will begin, therefore, with ourselves and so proceed through all the ranks of the church.”

It was the grief talking. Alexander was too much of a dyed-in-the-wool sinner to convert himself in the overnight manner he seemed to suggest.

Juan’s killers were never found, though the murder had all the hallmarks of a contract killing. In addition, though, there was talk that nine years after making it, Cesare Borgia had carried out his threat and killed the brother he so fiercely envied.

The murder of Juan Borgia, Duke of Gandia, remains a chilling enigma whispered through the centuries. Theories swirl like mist over the Tiber, each one casting a different shadow on the Borgia family’s tumultuous reign. Did his own brother Cesare, fueled by jealous ambition, lash out in the moonlit streets? Was it a vendetta orchestrated by the rival Orsini clan, eager to settle an old score? Or did Lucrezia Borgia, famed for her wit and cunning, play a hidden hand in this tangled web of power and betrayal?

While history may never definitively paint the scene of Juan Borgia’s last moments, the enduring allure of these conspiracies lies in their reflection of a Renaissance Rome steeped in intrigue and moral ambiguity. The Borgias, with their intoxicating blend of wealth, influence, and ruthless pragmatism, offer a perfect canvas for speculation, their motives ever shifting in the flickering candlelight of half-truths and whispers.

But perhaps the most intriguing aspect of these theories is their invitation to delve deeper into the human condition. They remind us that the thirst for power, the sting of betrayal, and the tangled web of familial bonds can twist even the gilded lives of nobility into a macabre drama. So, while we may never know who plunged the dagger into Juan Borgia’s heart, the enduring echoes of these conspiracies offer a glimpse into the dark desires and hidden tensions that simmer beneath the surface of any grand historical narrative.

Ultimately, the conclusion lies not in finding a singular culprit but in appreciating the enduring mystery itself. It is a testament to the enduring allure of power, the depths of human complexity, and the shadows that forever dance at the edges of even the most luminous historical figures.