After the divisive Civil War, 1861-65, The U.S.A. was faced with the challenge of rebuilding both the South, the relationship between states, and the federal government.

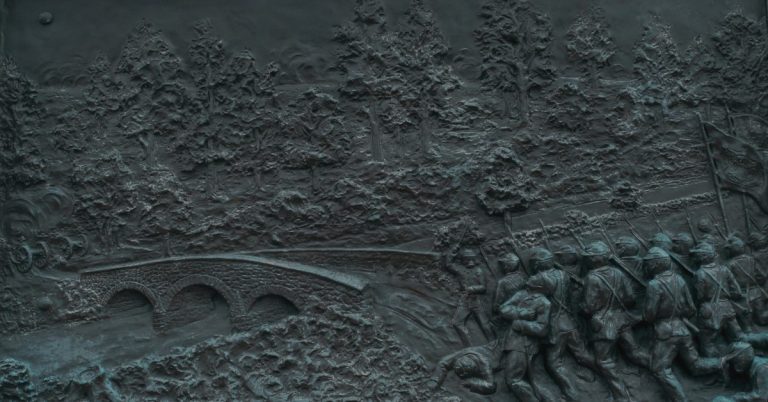

The year 1865 represented the last days of the Confederacy. The larger and better-equipped Union forces had successfully enforced a blockade on the Confederate States via land and sea. Federal troops had either occupied or destroyed all of the major industrial areas, which caused starvation and riots against the Confederate government. On March 20, 1865, the Southern government resorted to arming the slaves in a last-ditch effort to equalize the manpower disadvantage.

Union General William Sherman’s army took Atlanta and marched northward through the Carolinas, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake. Confederate General Lee was forced to surrender one of the last main rebel armies at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. General Johnston surrendered to Sherman on April 18, and the remaining Confederate forces surrendered to General Canby at Citronelle, Alabama, and in New Orleans.

In the meantime, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theater on April 14 while enjoying a production of “Our American Cousin.” Vice President Andrew Johnson succeeded to the presidency.

The Key Questions of the Reconstruction Plan

There were two major issues to be resolved once the Confederacy had been defeated:

- Were the rebel States still a part of the United States?

- Was the President or the Congress responsible for Reconstruction?

Former President Lincoln had always claimed that these eleven states had never left the Union. In 1862, he appointed provisional governors in Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

As early as December 8, 1863, he had already announced a plan of Reconstruction:

- Amnesty to all Southerners who would take an oath of loyalty.

- Recognition of state governments where 10% of the pre-war electorate took the oath and renounced slavery.

Louisiana and Arkansas took these steps in 1864, but Congress refused to let their representatives sit in the House. President Johnson adopted Lincoln’s plan and recognized the loyal governments in Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia, which Lincoln had set up. By December of 1865, every Confederate State except Texas had taken the steps. Texas was confirmed on April 6, 1866, and on December 6, President Johnson announced to Congress that the Union was restored.

Congress, however, refused to endorse what Johnson had done. A joint committee of six senators and nine representatives was formed instead to oversee the management of the former Confederacy. The committee considered the confederate states to be “conquered provinces,” and they were effectively put under the trusteeship of Congress.

Key Amendments and Legislation during Reconstruction

On December 18, the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified by 27 states and formally proclaimed. However, a New Freedmen’s Bureau had to be set up on February 19, 1866, in order to protect freed slaves from the harsh “Black Codes” being enacted in some states. These Black Codes effectively tied the freed slaves to the land on which they lived and worked.

Later that year, on April 9, Congress passed a Civil Rights Act that bestowed citizenship on Afro-Americans. The Act granted the same civil rights to all persons born in America (except Indians). Johnson vetoed the bill because he said that it infringed on the rights of those states that were not represented in the House. The Act was passed over Johnson’s veto, but the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional.

The Joint Committee then formulated the 14th Amendment to the Constitution in order to get around the apparent unconstitutionality of the Civil Rights Bill. It passed Congress on June 13 and was submitted to the states for ratification.

The Amendment defined American citizenship and included Afro-Americans. It provided Federal protection to freedmen whose rights could not now be limited by state governments. Ratification was denied by most of the southern states but was made a requirement for readmission into the Union. Tennessee accepted the Amendment, but the other southern states awaited the upcoming congressional elections and possibly a more sympathetic congress.

Johnson’s Republicans captured a two-thirds majority in both houses, giving the Republican Radicals control over Reconstruction. This was Johnson’s party, but these radicals were much more antagonistic towards the South than he. On March 2, 1867, Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act over Johnson’s veto. Martial law was declared over the former Confederate states, which were divided into five regions.

The new requirements for states to be readmitted to the Union were ratification of the 14th Amendment and universal suffrage, guaranteeing that Afro-Americans would be given the right and opportunity to vote. In the Omnibus Act, June 22-25, 1868, seven states met the requirements and were readmitted to the Union.

These were Arkansas, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina and South Carolina.

Georgia soon returned to military rule when all of the Afro-American representatives were dismissed from the state legislature. It was allowed to return to self-rule only when the state ratified the Fifteenth Amendment, guaranteeing equality for the freed slaves and allowing the Afro-Americans to return to the House.

Johnson’s Role and the Rise of Radical Republicans

Despite being vetoed by Congress, Johnson faithfully executed their decisions. He appointed military commanders who led 20,000 troops (including Afro-American militia) into the South. Governments that he had previously set up were displaced. 703,000 Afro-Americans and 627,000 whites were registered as voters.

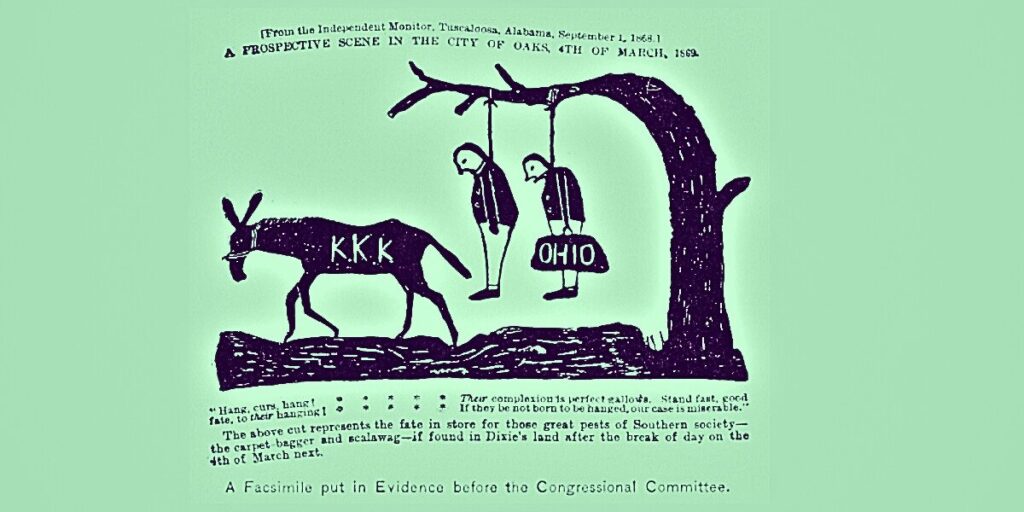

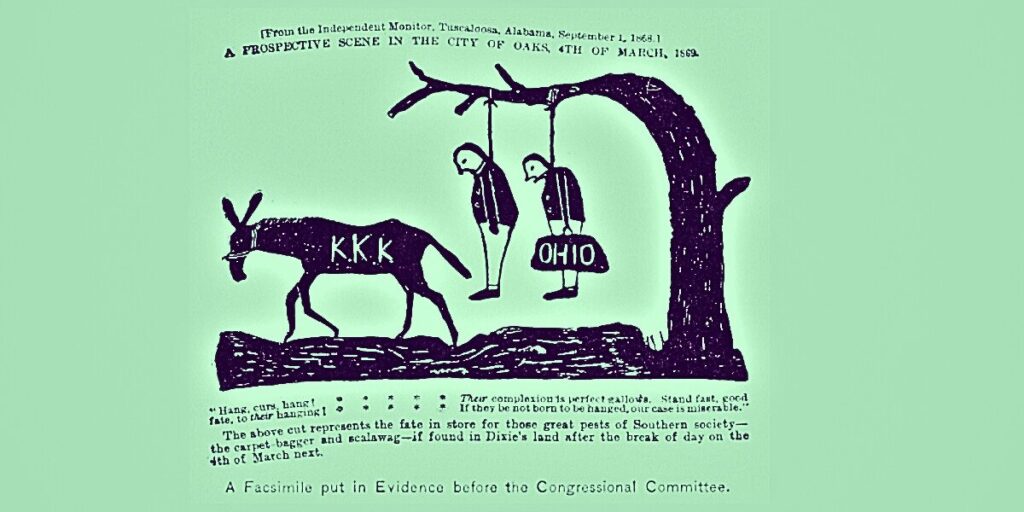

In Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, black voters were in the majority. In other states, a black-white coalition formed under the Radical banner. Southern whites allied with the Radicals were called “scalawags.” Northerners who went south to assist in Reconstruction were called “carpetbaggers.”

Meanwhile, Radicals in Congress consistently overrode Johnson’s vetoes and placed some important limitations on his executive power. Johnson was prevented from naming judges to the Supreme Court and deprived of being the “Commander in Chief” of the armed forces.

The Covode Resolution of February 24, 1868, was passed in the House by a vote of 126-47 and called for the impeachment of the President. The charges included alleged violations of the Tenure of Office Act and the Command of the Army Act and bringing disgrace upon Congress.

The impeachment vote, however, did not arrive at the required two-thirds majority.

The Supreme Court played a huge role in determining the legality and constitutionality of many of the laws that were passed during Reconstruction. The court decided that it was unconstitutional to set up martial law where civil courts were in operation. In Texas vs. White, 1869, the court upheld Lincoln’s position that the Union was indivisible and indissoluble. The court also decided that the loyalty oaths were wrong and invalidated them.

Reflecting on the Complexities of the Civil War Reconstruction Plan

The Reconstruction era, following the tumultuous years of the Civil War, was a period of profound transformation and challenge for the United States. This critical phase in American history was marked by the nation’s struggle to rebuild the South, redefine state-federal relations, and integrate millions of freed slaves into the social and political fabric of the country. The complexities of this era were underscored by the conflicting visions and political tug-of-war between Presidents Lincoln and Johnson and a Congress determined to impose its own approach to rebuilding the nation.

The legislative milestones, including the ratification of the 13th and 14th Amendments, were monumental in shaping the future of the United States. They laid the groundwork for civil rights and liberties that would continue to evolve over the following centuries. However, the period was also marred by resistance, as seen in the implementation of Black Codes and the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau to protect the rights of newly freed African Americans.

The Supreme Court’s role in adjudicating the constitutionality of Reconstruction laws further highlighted the complexities of this era. Their decisions played a crucial part in determining the trajectory of the nation’s recovery and the extent of federal authority over the states.

In retrospect, the Reconstruction era was a pivotal moment in American history, setting the stage for the ongoing struggle for racial equality and civil rights. It was a time when the nation grappled with its identity and the meaning of freedom and equality. The challenges and triumphs of this period offer enduring lessons on the intricacies of nation-building and the pursuit of a more equitable society.