Although little known, the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 had profound effects on the history of the United States, including the role of the federal government.

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 is little remembered today, but its impact had profound effects on the future of the United States. Among them was a new relationship between the federal government and the states, dissension within the administration of George Washington, which would lead to the demise of his popular Federalist Party and the birth of a new political party that lives on to this day.

The Whiskey Rebellion also marked the first and only time that a president of the United States put on a military uniform to personally lead troops into battle.

The Seeds of Rebellion

Although the Whiskey Rebellion had broken out in 1794, it had been simmering for several years. Following the Revolutionary War, the federal government agreed to assume the war debt of the states in exchange for moving the nation’s capital from Philadelphia south to a swampy mosquito ridden area on the Potomac which is today known as Washington, D.C..

In order to help pay these war debts, the Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, placed a 25% excise tax on all liquor sold in the United States. This tax was vehemently opposed by farmers in the western areas of all states south of New York because they relied upon producing whiskey for their livelihoods. This was because transporting grain, as liquor, was much easier to transport than grain.

This unpopular tax represented a large imposition of federal authority at the time. In fact, Thomas Jefferson resigned from his administration post as Secretary Of State, in part due to his protest against the whiskey tax. After Jefferson’s departure, he went on to help form the Democratic-Republican Party, which supported the State’s rights against the power of the federal government. This was to lead to the demise of the Federalist party of Washington and Hamilton.

By 1794, the Whiskey Rebellion had broken out into the open. Tax collectors who were sent to western Pennsylvania were routinely threatened, tarred, and feathered, making it impossible to collect the whiskey tax from that area.

In June of that year, local officials ordered the arrest of the leaders of the whiskey tax resistors. However, all this did was incite the farmers of western Pennsylvania to more violence.

A month later, in July, the commander of the local militia, James McFarlane, was shot and killed by federal troops defending a besieged tax official named John Neville. This enraged the local anti-tax settlers, who went on to burn down the buildings belonging to Neville as he was hustled to safety by the federal troops.

The Federal Response

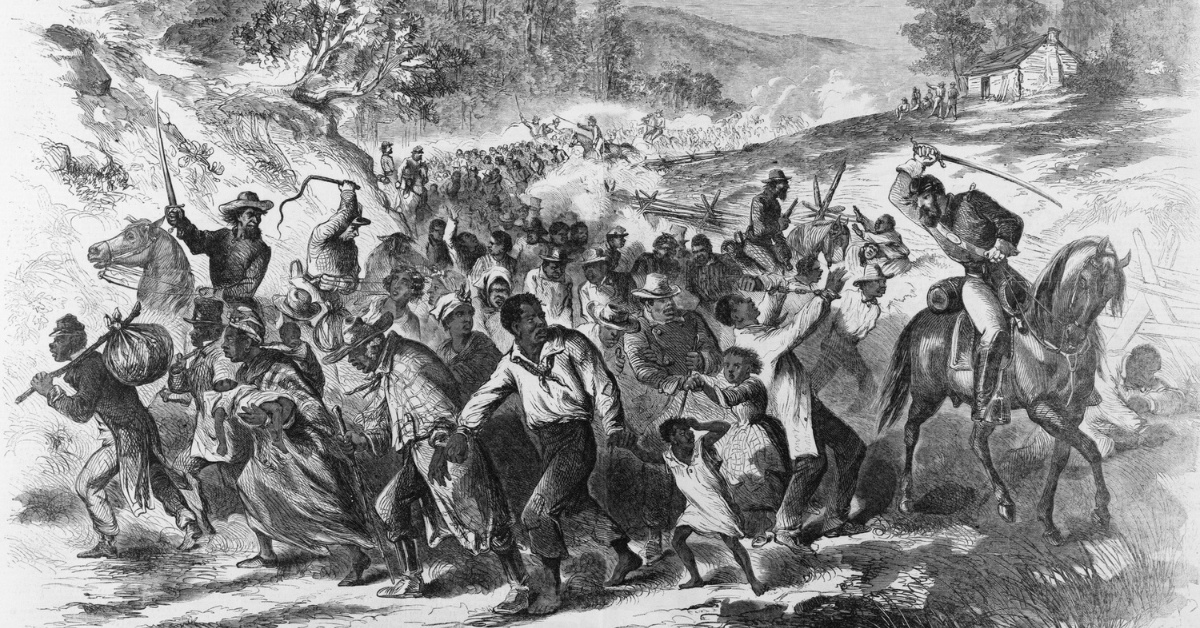

In reaction to this, President George Washington recruited a militia force in August 1794 from Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia. This force was derisively nicknamed the “Watermelon Army” by the western Pennsylvania whiskey tax rebels.

When negotiations between federal commissioners and the rebels failed, Washington himself put on his Revolutionary War uniform again and personally led the army of over 12,000 troops into Western Pennsylvania. This force easily put down the Whiskey Rebellion because the farmers, faced with such a large force and notable commander, quickly dispersed. Most of the prisoners that Washington’s army captured were later released due to lack of evidence.

Two of the rebels were convicted of treason but were subsequently pardoned by Washington, who perhaps did not want to leave bad feelings lingering from this greatest crisis of his administration.

The Aftermath and Legacy

The aftermath of the Whiskey Rebellion had far-reaching consequences for American politics and society.

The federal government’s successful suppression of the insurrection reinforced the authority of the Constitution and the laws enacted under it, affirming the principle that while peaceful protest was acceptable, armed resistance to lawful authority was not. This distinction would inform the United States’ approach to civil unrest for centuries to come.

The rebellion also had significant political ramifications, deepening the divide between the Federalist and Republican parties.

Federalists, who supported a strong central government, saw the rebellion’s suppression as a vindication of their policies. In contrast, Republicans, who championed states’ rights and limited federal power, viewed Washington’s military response as an overreach and a threat to individual liberties.

Moreover, the Whiskey Rebellion underscored the ongoing tensions between the eastern seaboard’s urban commercial centers and the rural, agrarian frontiers. This cultural and economic divide would continue to shape American politics and society, contributing to the complexity of the nation’s identity and governance.

Although the Whiskey Rebellion did mark the supremacy of the federal government, it also made the citizens of the states wary of this power. The question of states’ rights versus the powers of the federal government was not to be fully resolved until after the Civil War.

In conclusion, the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 was more than a tax protest; it was a critical juncture in the development of the United States as a nation. It tested the resilience of the newly formed federal government, challenged the limits of executive power, and set precedents for addressing civil disobedience.

The rebellion’s suppression affirmed the rule of law and the authority of the federal government, but it also highlighted the delicate balance between enforcing order and preserving individual freedoms. As such, the Whiskey Rebellion remains a defining chapter in American history, offering valuable lessons on governance, citizenship, and the ongoing quest for a more perfect union.