Famous paintings reflect so much more than pure, unbridled talent from the artist. When a painting evidently surpasses the role of a placeholder in a rogue museum gallery and becomes something not only to talk about but also to teach, the work has elevated into a masterpiece. Below is a compilation of paintings over the course of history that have changed the world through their various techniques or intense content.

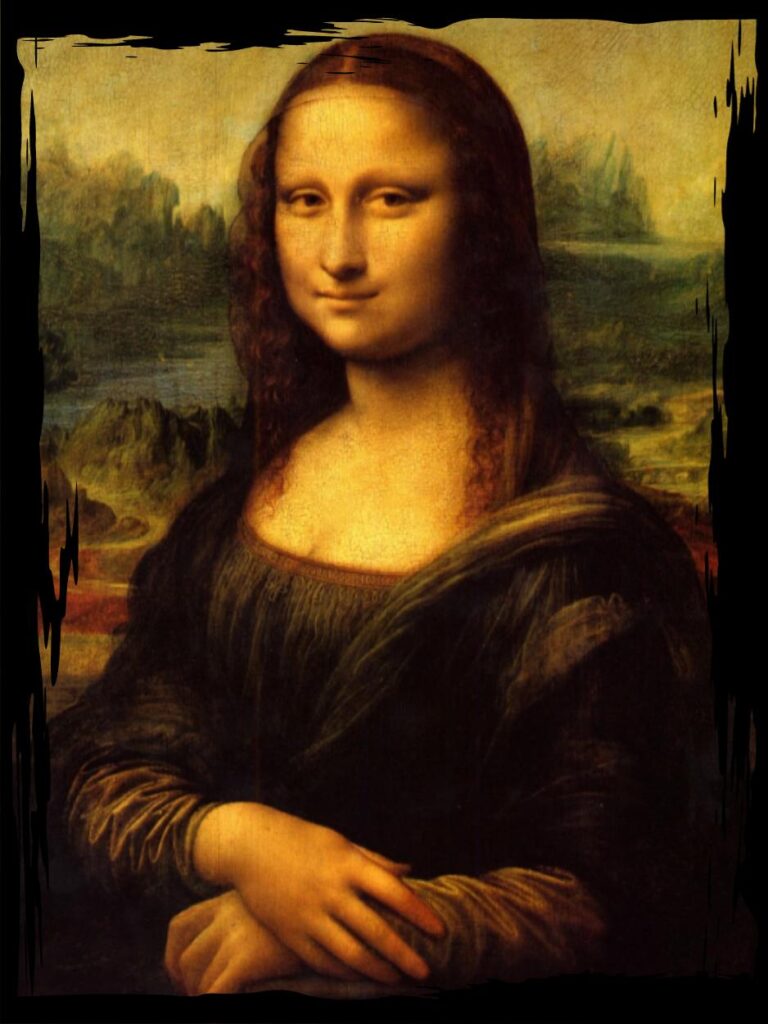

The Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci – 1503-06

The Mona Lisa is unquestionably the most famous smile in the world. With this unforgettable painting, Da Vinci set a new pattern and a new formula for portraiture, showcasing a view that was neither profile nor full face. Mona Lisa casually turned to smile at the spectator, with the weight shifted onto the arm of the chair.

Da Vinci has presented the woman as mysterious, mature, and filled with secrets she is keeping to herself. Her folded hands are an informal touch of grace, and her height against the landscape is a subtle touch of grandeur. There is a monumentality within this composition, for the painting was among one of the first portraits to depict the sitter before an imaginary landscape, and Da Vinci was one of the first painters to utilize aerial perspective. She is seated with dark pillar bases on either side; behind her, a vast landscape recedes to icy mountains and winding paths, and a distant bridge gives only the slightest indication of human presence.

The sensuous curves of the woman’s hair and clothing are echoed in the undulating imaginary valleys and rivers behind her. Blurred outlines, a graceful figure, and dramatic contrasts of light and dark: all these features are characteristic of Leonardo’s style, resulting in an overall feeling of calm. We are witnessing the ultimate connection between humanity and nature.

The School of Athens, Raphael – 1509-11

The School of Athens revolutionized contemporary portrait-making with Raphael’s clever approach to enlarging the architecture of the pictorial space, then spreading and deepening the extent with figures. This famous Italian fresco was commissioned to decorate rooms in the Vatican.

Raphael’s masterpiece is the perfect embodiment of the classical spirit of the Renaissance. Plato and Aristotle are central figures in the scene, flagged by the ultimate elements of pure Roman architecture. Nearly every Greek philosopher can be found within this painting, thanks to Raphael providing the viewers with a handy host of symbols as clarification tools.

Plato and Aristotle (his student) are both holding modern, bound copies of their books in their left hands and gesturing with their right. Plato is old, grey, and filled with wisdom; Aristotle is in the throes of mature manhood, handsome, and well-dressed. This powerful flow of space towards the viewers can be interpreted as a divergence of the two philosophical schools.

Indeed, The School of Athens is telling the viewer of the infamous Italian Renaissance, an era in which there was both enormous new wealth flooding into Italy and a consequent encouragement for the arts by the intellectual elite class. Religious fervor was at its ultimate height, which Renaissance thinkers were able to harmoniously mix with an adoration of Ancient Greek and Roman culture as the roots of European civilization.

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo – 1536-41

This painting is one of the most recognized and imitated images of all time! Painted on the ceiling of The Sistine Chapel, it provided countless European artists with a treasure trove of images and ideas to plunder. The ceiling tells the story of Genesis (filled with prophets, saints, and sinners) and Adam at the moment of creation.

This unbelievable fresco (by undoubtedly the Italian Renaissance master) showcases a dramatic rendering of heaven and hell, resurrection, and a descent into the Underworld. The souls of the humans rise and descend to their fates, as judged by Christ and the surrounding prominent saints. Of course, this is a fitting subject for 1530s Rome and the judgmental impulses of the Counter-Reformation.

What was groundbreaking about Michelangelo’s vision of the event was showing them in their nudity, stripped bare of rank. He portrayed the separation of the blessed and the damned by painting the saved ascending on the left and the damned descending on the right. The ceiling is dominated by tones of fresh and cerulean blue sky and, of course, an imaginative vision that prevails above all within this masterpiece.

The picture radiates outwards from the central figure of Christ, deciding the destiny of the human race. The dead are awakened by angels and their trumpets, while the Archangel Michael reads from The Book of Souls to determine who is to be saved. The sinners, unfortunately, are cast into the Underworld, with their faces and bodies contorted in agony.

Venus of Urbino, Titian – 1538

Titian changed the game with the way he portrayed his secular subjects, often sexual and mischievously mythological, conveying delight in erotic pleasure. Titian transformed the history of art and of patronage, enabling kings and princes of the church to commission sexual seductions as readily as crucifixions. Ultimately, he widened the range of subjects open to the painter.

In the case of the Venus of Urbino, our female subject is portrayed as more courtesan than goddess. Venus has been painted in oil, a luxurious new medium capable of richer and more intriguing surfaces. We witness a nude young woman, identified with the goddess Venus, reclining on a bed in the sumptuous surroundings of a Renaissance palace. Titian has domesticated Venus by moving her to an indoor setting, engaging her with the viewer, and making her sexually explicit.

The work is devoid of any classical or allegorical trappings, and Venus displays none of the attributes that said goddess is supposed to represent. The painting is unapologetically erotic, with Venus staring straight at the viewer, unconcerned with her nudity. To further hammer the point home, Titian contrasts the straight lines of the architecture with the curves of the female form. Due to the wise use of color and its contrasts, as well as the subtle meaning and allusions, Titian truly achieved his goal of representing the perfect Renaissance woman who, just like Venus, becomes the symbol of love, beauty, and fertility.

The Calling of St. Matthew, Caravaggio – 1599-1600

Caravaggio set himself apart from the previous acclaimed painters from the get-go with his quirky choice of androgynous youths in ambiguous, erotic, and illusionist situations.

In The Calling of St. Matthew, Caravaggio has depicted the moment at which Jesus Christ inspires Matthew to follow him. Matthew, the tax collector, is sitting at a table with four other men. Jesus Christ and Saint Peter have entered the room, and Jesus is pointing directly at Matthew. A beam of light illuminates the faces of the men at the table who are looking at Christ, bringing together two distinct worlds: the power of the immortal faith and the alternate mundane reality.

Caravaggio’s use of light and shadows adds drama to this image and gives the figures a quality of immediacy. This steeply diagonal composition has its drama enhanced by the contrasts in light and shadow (stemming from the candle and the lamp as the ultimate light sources). Caravaggio has exhibited a fervent adherence to realism, emphasized by the less aesthetically pleasing details, such as the dirty feet and fingernails.

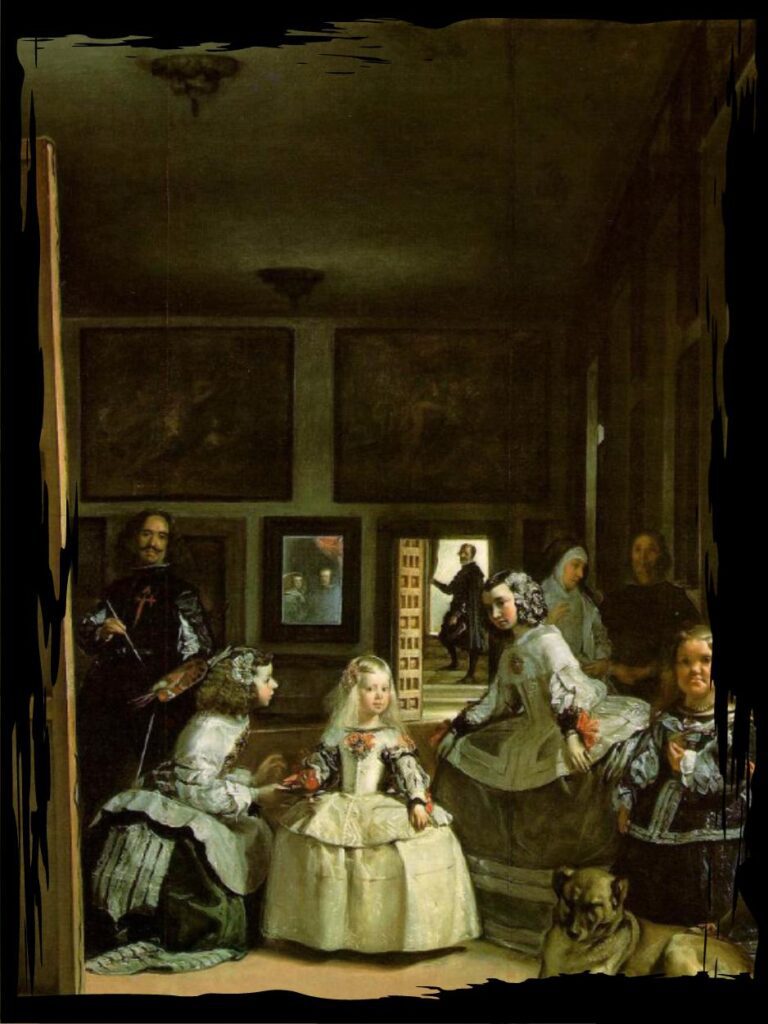

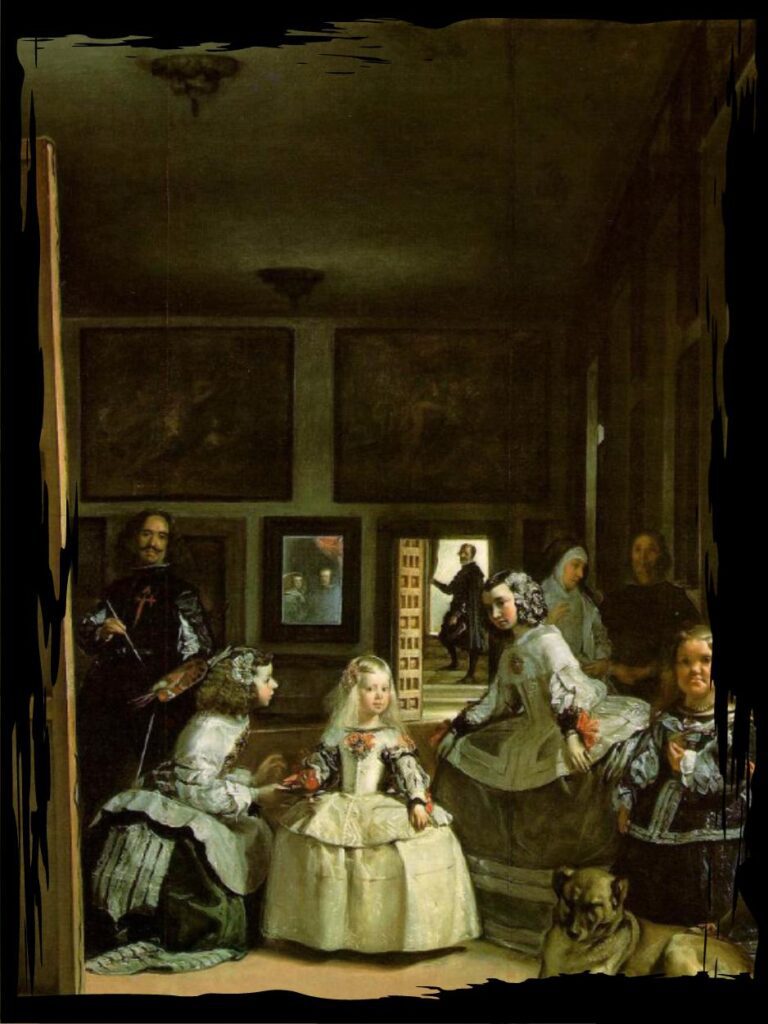

Las Meninas, Velazquez – 1656

Velazquez’s ingenious composition, in which he portrays himself in the act of painting the King and Queen of Spain, has been the focal point of art historical perspective for years. What is interesting about Velazquez’s depiction of the King and Queen Is that they, in fact, stand with us as spectators outside of the picture’s space and can only be seen reflected in a small mirror on the rear wall of the studio. The focal point is the young girl, the royal daughter, who will usher in the future of Spain as a beacon of hope and modernity.

Velazquez has inserted not only his physical form but also his intellectual beliefs about the hierarchy and importance of the aristocracy within the painting. This complex and enigmatic composition raises questions about reality and illusion and consequently creates an uncertain relationship between the viewer and the figures depicted.

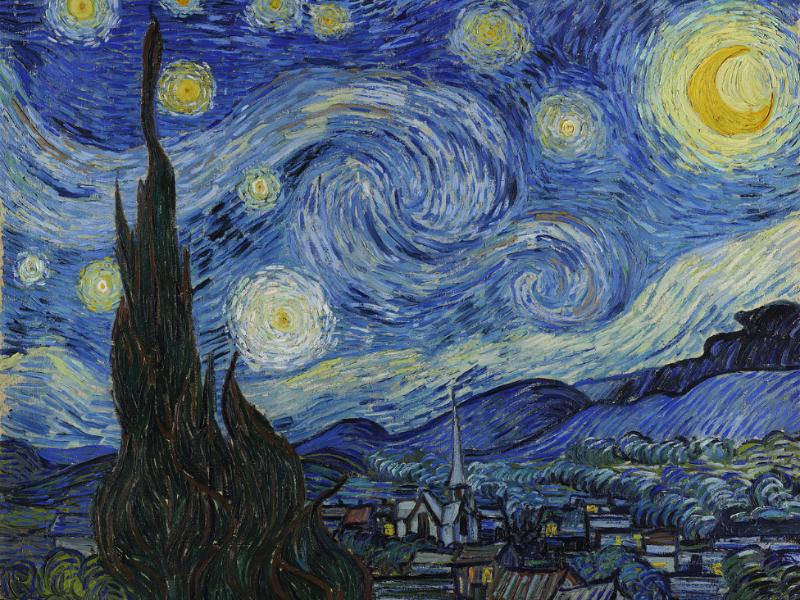

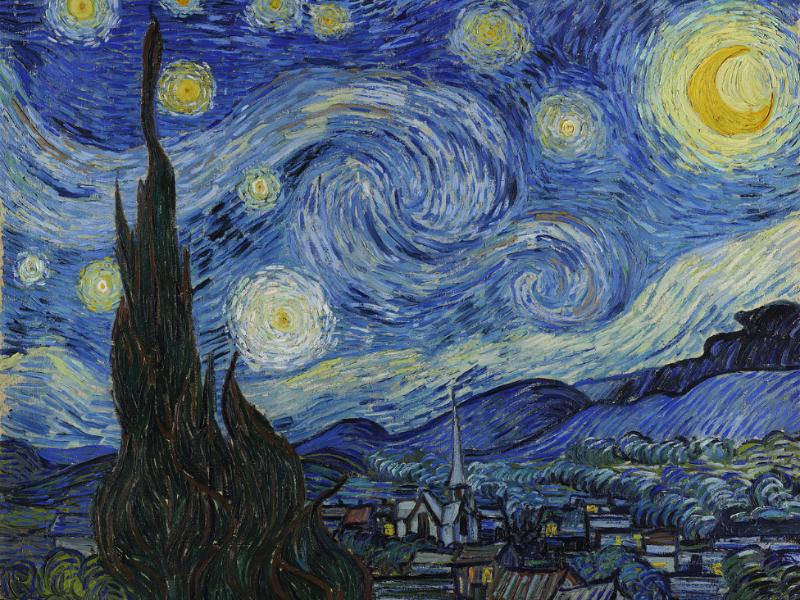

The Starry Night, Van Gogh – 1889

Van Gogh’s Starry Night is the perfect example of the Impressionist painting movement, which threw caution to the wind with its sweepingly open brushstrokes and entirely new way to showcase color. Impressionism emphasized the sentiment and the poetry behind an image rather than merely representing what the artist could see.

In the aftermath of Van Gogh’s 1888 breakdown that resulted in the self-mutilation of his left ear, he voluntarily admitted himself into an asylum. The scene unfolding before us in Starry Night depicts the view from the east-facing window of Van Gogh’s asylum room at Saint-Remy-de-Provence just before sunrise. There is a lot of beauty to behold, from the low rolling hills of the Alpilles Mountains to the majestic cypress trees (with associations of mourning and graveyards) to the turbulent and agitated moon and star-filled sky that swirls around the canvas-like rough waves. Beneath this expressive sky sits a hushed village of humble houses surrounding a church, whose steeple rises sharply above the undulating blue-black mountains in the background. This is the ultimate combination of direct observations, imagination, memories, and emotions.

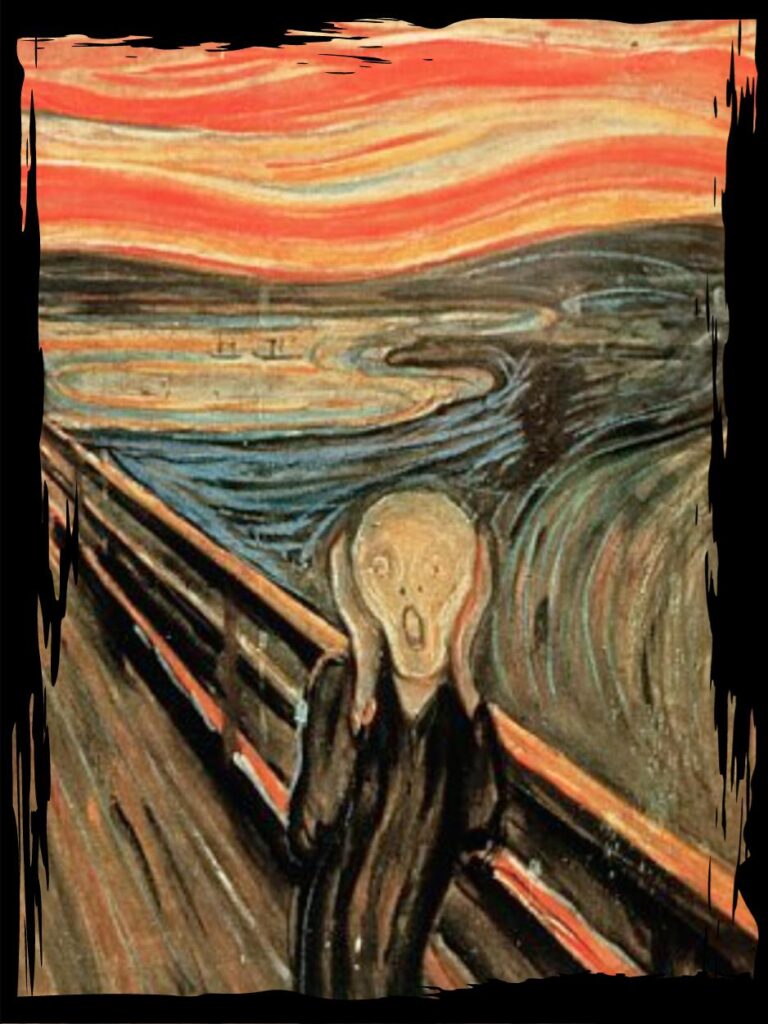

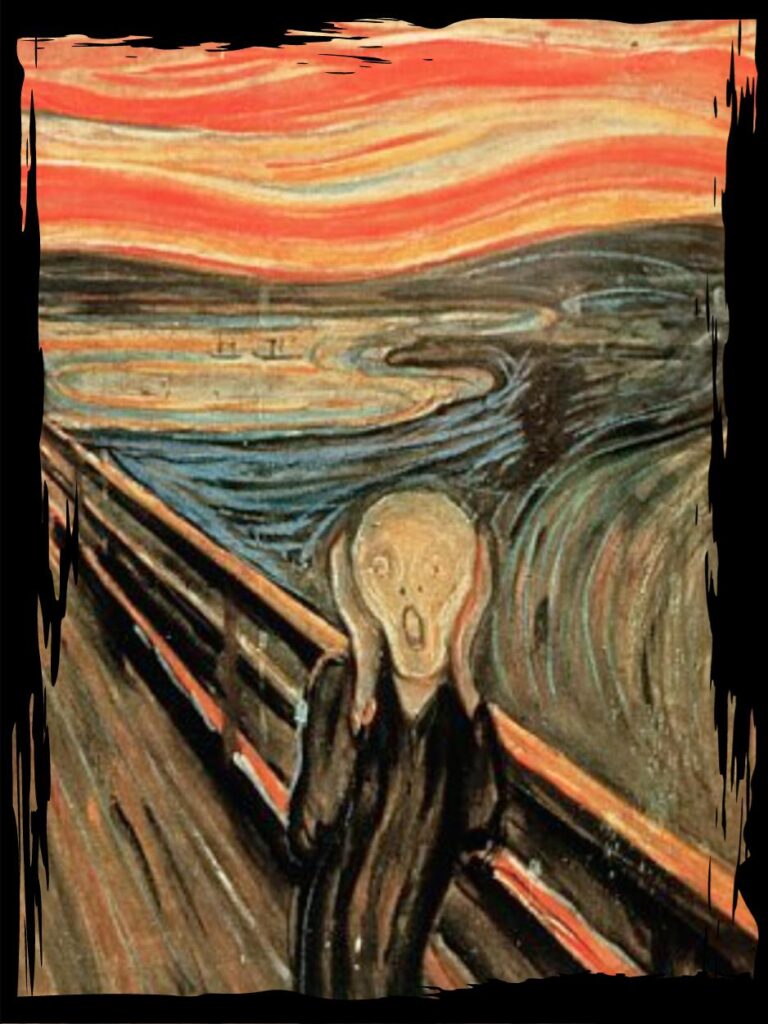

The Scream, Edvard Munch – 1893

This painting (that recently sold at auction for $120 million) is one of the most vivid, haunting, and iconic pieces of art ever made. Munch, a Norwegian Expressionist, evidently created a work from a fragment of his imagination overrun with very dark subject matter. The central figure is clearly suffering from a private moment of anguish and despair, while the people surrounding him appear to be blissfully unaware of his anxieties and demons.

The Scream is an icon of modern art, defining how we see our own age, wracked with anxiety and uncertainty. Munch has exhibited a psychologically charged and expressive style to transmit emotional sensations. One needs no further explanation for the figure’s deep-rooted pain; merely observe his flagrant anguish against a landscape with a tumultuous orange sky.

Marilyn Monroe, Andy Warhol – 1962

Undoubtedly one of Pop Art’s finest creations. Warhol was expertly able to show contemporary artists that they couldn’t avoid or ignore the foundational social changes affected by mass media. Whether he was exploring identity, vanity, sexuality, or fame, Warhol was a major player in the Pop Art movement that emerged in America and elsewhere in the 1950s and was outstandingly prominent over the subsequent two decades.

Warhol experimented with the technique of silkscreen printing, a popular method used for mass production. In employing this technique, Warhol moved away from the elitist avant-garde tradition and created a new marriage between art and commodity culture.

Soon after Marilyn Monroe’s tragic suicide in 1962, Warhol made a series of paintings to pay tribute to this film star and sex symbol that captured the world’s imagination and left an imprint and a void forever.

Guernica, Picasso – 1937

Picasso, arguably the most famous and prolific artist of the 20th century, created approximately 13,500 paintings and hundreds of thousands more prints, engravings, illustrations, and sculptures. No matter the medium or the style, Picasso had a hand in radically changing it all.

Picasso was an adamant opponent of the Nazi-German intervention in the Spanish Civil War, and Guernica—his masterpiece – was the physical embodiment of his hatred and distaste for the situation. Guernica is a fractured, monochrome composition from which all color has been drained. All living creatures, human and animal, are turned into tortured objects, decomposed, distorted, and shrieking in agony to the sky. We are bombarded with stark imagery, impetuous emotions, and a ferocious response to tragedy.

This palette of grey, black, and white shows the suffering of people, animals, and buildings wrenched by violence and chaos. The discarding of color intensifies the drama, producing a reportage quality as if the painting were a photographic record.

On the left, we see a wide-eyed bull standing over a woman who is grieving a dead child in her arms. The center of the canvas has been taken over by a horse falling in agony, as it has just been punctured through by a javelin. This large, gaping wound on the horse’s side is a major focal point of the painting. Underneath the horse lies a dead, dismembered soldier, his severed arm still grasping a shattered sword. Daggers replace the tongues of the bull, grieving woman, and horse, suggesting blood-curdling screams.

Guernica has become a universal and powerful symbol warning humanity against the suffering and devastation of war. Looking at this painting is entirely consuming, for it truly depicts the tragedies of war, particularly against innocent civilians.

Lavender Mist, Jackson Pollock – 1950

Pollock is perhaps the most recent artist to embody the artistic revolution, thanks to his famous drip paintings, which allowed him to become instantly identifiable. Pollock became the figurehead of the Abstract Expressionist movement and helped radically change the world’s definition of what constitutes ‘good art.’

Abstract Expressionism can be regarded as the final step in a painting’s inevitable reduction to its most essential elements. There is an unmatched purity to Pollock’s atmospheric, gravity-free color fields that only the eye can traverse. His subverted figurative painting changed the world of art history in an unprecedented way, primarily due to his technique. Pouring and dripping paint is, after all, an immediate means of creating art; the paint literally flows from the chosen tool upon the canvas. By defying the convention of painting on an upright surface, Pollock added a new dimension to work by being able to view and apply paint to his canvases from all directions. By painting in this manner, Pollock moved away from figurative representation and challenged the Western tradition (and foundation) of using easel and brush.

Each of the above paintings has had such an intense impact and effect on the world of art as a whole that they shall never be forgotten. Their techniques, subject matter, and prowess still resonate so strongly to this day that it is no surprise they influenced the world and helped redefine everything prior.